THE THIRD MAN (1949)

THE THIRD MAN (1949)

From the moment the first audiences saw the opening image of Anton Karas’s zither filling the screen with the nerve-jangling Harry Lime Theme (before, indeed, they had heard the word “zither”), they knew that with the second collaboration between director Carol Reed and author Graham Greene they were in for something special. At its end they recognised they’d seen a near-perfect work, what we now call a noir classic. The title rapidly entered the language and took on new meanings as the careers of Greene as wartime intelligence agent and Kim Philby as cold war traitor became linked.

The story features an evil, charismatic anti-hero who fakes his own death and makes his home in a Viennese sewer, and ends with its dull, perplexed leading man being silently snubbed by the beautiful, unsmiling heroine in a deserted cemetery. This new print does full justice to Robert Krasker’s dazzling, Oscar-winning black-and-white photography and its exhilaratingly forlorn postwar Vienna, and it’s accompanied by two excellent documentaries, one about the making of the movie and its afterlife, the other about the career of Greene, then at the height of his power as both a novelist and screenwriter.

The Third Man is essentially Greene’s movie and it’s permeated with the art of Catholic beliefs, his feeling for immanent good and evil, his fascination with storytelling, with men in flight and pursuit, with life lived on what Robert Browning called (in a favourite quote of Greene’s) “the dangerous edge of things”. But this is a movie to which many contributed, and it has grown richer with the passing years. Producer Alexander Korda came up with the setting – a corrupt, politically divided Vienna – as the perfect location for Reed and Greene’s follow-up to The Fallen Idol, which he’d produced. Greene devised the plot, which had its origins in a single startling image he’d jotted down on the flap of an envelope: “I had paid my last farewell to Harry a week ago when his coffin was lowered into the frozen February ground, so that it was with incredulity that I saw him pass by without sign of recognition, among the host of strangers in the Strand.” Korda’s co-producer David Selznick provided money, the prospect of wide distribution in America, two stars from his own stable (Alida Valli and Joseph Cotten, who came to represent the soul of a surviving Europe and a dangerously innocent America), and an anti-Soviet undercurrent that Reed and Greene quietly buried, at least in the British version.

Reed used the time, while waiting for Welles to show up, to experiment with tilted cameras and surreal shadows

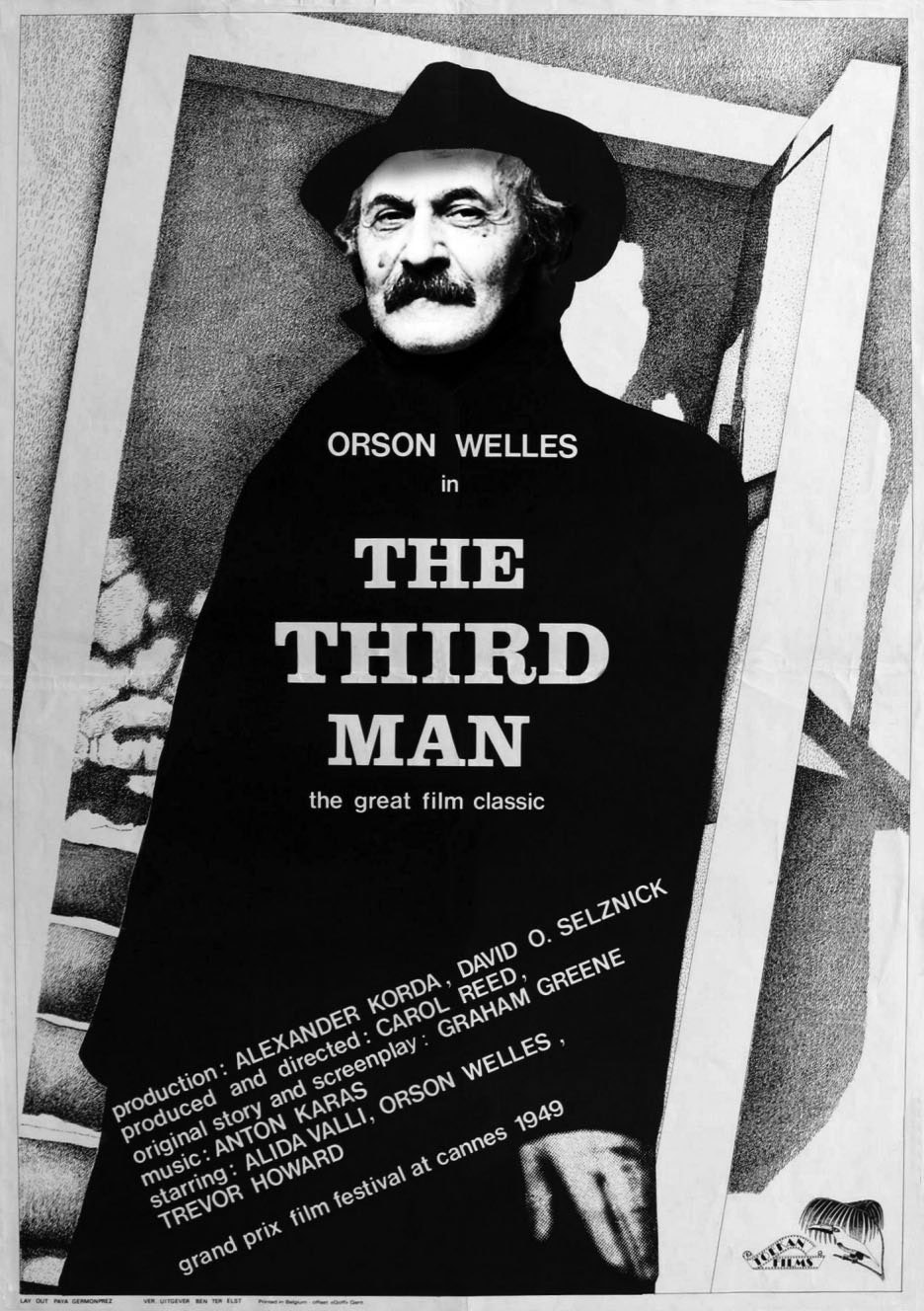

Then there’s Orson Welles as Harry Lime, leader of the gang peddling adulterated penicillin in Vienna. He dominates the film both by his presence and his absence. He was difficult to pin down, even for his brief appearances. Reed used the time shooting at night, while waiting for Welles to show up, to experiment with tilted cameras and surreal shadows in narrow, gleaming nocturnal streets that became one of the film’s hallmarks.

In 1979, during a BBC radio programme to mark Greene’s 75th birthday, I asked him which film based on his work had given him the greatest satisfaction. I expected him to say The Third Man. Instead he named The Fallen Idol, going on to explain that The Third Man was a director’s film, while The Fallen Idol was a writer’s picture. One can understand why, even while disagreeing with him. It was Carol Reed who was immediately fascinated on hearing Karas play the zither in a Viennese cafe and decided to bring the musician to London and settle for this single instrument. It was also Reed who decided to drop Greene’s original ending of a reconciliation between Holly Martins and Anna and opt for the bleak conclusion that the author thought audiences would find boring as they reached for hats under their seats. Reed also decided that there would be no subtitles to translate the German dialogue that Cotten’s Martins couldn’t understand: like him the audience would have to work out what people were saying.

There is perhaps another reason why Greene might have had certain reservations about The Third Man. Every time you see the film over the years you notice something new. You suddenly become aware, for instance, of the way the strings of the zither at the beginning are later echoed in the cables of the suspension bridge seen from above in the sequence in which the conspirators meet with Lime on the Danube, and later the wires of the Great Wheel in the Prater pleasure park, where Lime and Martins are to have their crucial meeting looking down on the world. Great spiders’ webs, perhaps, or the strings of giant marionettes?

Greene, despite the similarities between their works, had a loathing for Hitchcock’s films. But one notices the influence of The 39 Steps on the confrontation between Martins and Lime’s henchmen at the British Council lecture, and one also learns from Greene’s screenplay that the character of Crabbin (the cultural bureaucrat played by Wilfrid Hyde White) was originally written for Basil Radford and Naunton Wayne in the Charters and Caldicott personae created for Hitchcock’s The Lady Vanishes.

But the most striking influence that occurred to me only decades after first seeing The Third Man is its likely debt to Eric Ambler’s The Mask of Dimitrios, which turns upon a British thriller writer journeying to Istanbul to see a brilliant criminal who has disappeared after faking his death. There are several apparent allusions to Ambler’s book in the film (including one by Ambler’s friend, Carol Reed, to prewar Istanbul in the film’s stage-setting introduction), and Greene includes a chapter from The Mask of Dimitrios in his anthology, The Spies Bedside Book. During an onstage interview with Ambler at the National Film Theatre in he 1990s, I asked him if he’d ever noticed the resemblance. “I have indeed,” he replied, but sadly I never got around to pursuing the matter, and Ambler died soon afterwards.

The Germans have a term for movies set among the ruins of postwar cities – “Trümmerfilm” or “rubble films”. Notable in this sub-genre are such pictures of the 1940s as The Murderers Are Among Us (Wolfgang Staudte, 1946) and Germany Year Zero (Roberto Rossellini, 1948). The Third Man, deeply influenced by Italian neorealism, is arguably the most significant British example, though it has a close contender in Reed’s Odd Man Out (1947), shot on blitzed sites in Belfast, and Charles Crichton’s seminal Ealing comedy Hue and Cry (1947). Ken Adam, production designer on the early Bond movies, cut his teeth working on rubble films such as Obsession (1949) and Ten Seconds to Hell (1959).

Phillip French, The Guardian.

Further Reading: https://cinephiliabeyond.org/t...