Next Screening

Ciné-Real hosts regular 16mm film screenings in London with rare prints and real film projection.

THIS MONTH: January at Ciné-Real dives into the shadowy world of film noir. Ambiguous morality, sharp dialogue, and unforgettable black and white cinematography, all projected from original 16mm prints on the big screen.

Wednesday 21st January

The Third Man on original 16mm, 7.30pm

Sunday 25th January

The Maltese Falcon on 16mm, 2pm

Thursday 29th January

The Third Man on original 16mm, 7.30pm

All screenings are introduced by the Ciné-Real team, celebrating the texture and atmosphere of classic noir as it was meant to be seen.

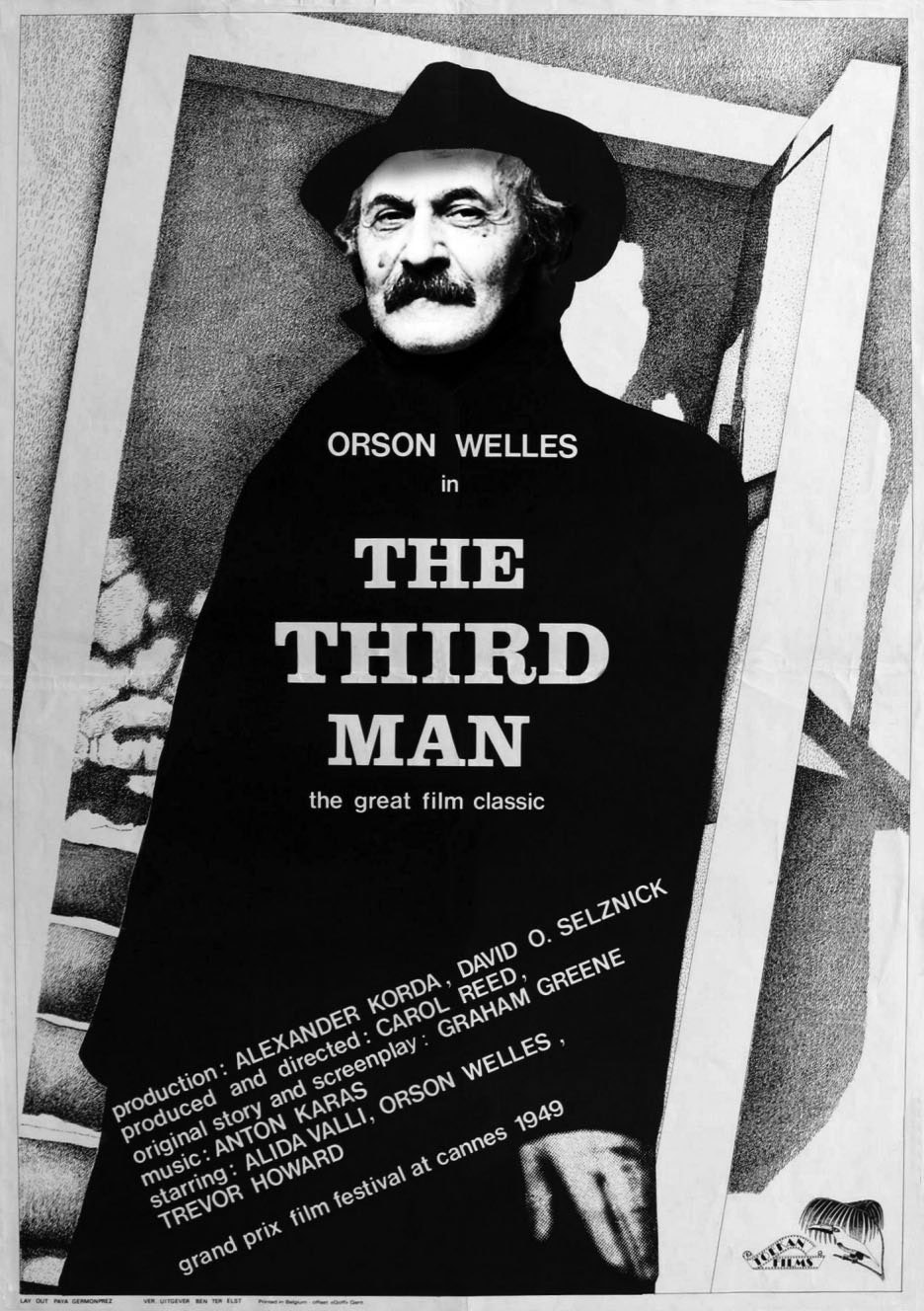

THE THIRD MAN (1949)

From the moment the first audiences saw the opening image of Anton Karas’s zither filling the screen with the nerve-jangling Harry Lime Theme (before, indeed, they had heard the word “zither”), they knew that with the second collaboration between director Carol Reed and author Graham Greene they were in for something special. At its end they recognised they’d seen a near-perfect work, what we now call a noir classic. The title rapidly entered the language and took on new meanings as the careers of Greene as wartime intelligence agent and Kim Philby as cold war traitor became linked.

The story features an evil, charismatic anti-hero who fakes his own death and makes his home in a Viennese sewer, and ends with its dull, perplexed leading man being silently snubbed by the beautiful, unsmiling heroine in a deserted cemetery. This new print does full justice to Robert Krasker’s dazzling, Oscar-winning black-and-white photography and its exhilaratingly forlorn postwar Vienna, and it’s accompanied by two excellent documentaries, one about the making of the movie and its afterlife, the other about the career of Greene, then at the height of his power as both a novelist and screenwriter.

The Third Man is essentially Greene’s movie and it’s permeated with the art of Catholic beliefs, his feeling for immanent good and evil, his fascination with storytelling, with men in flight and pursuit, with life lived on what Robert Browning called (in a favourite quote of Greene’s) “the dangerous edge of things”. But this is a movie to which many contributed, and it has grown richer with the passing years. Producer Alexander Korda came up with the setting – a corrupt, politically divided Vienna – as the perfect location for Reed and Greene’s follow-up to The Fallen Idol, which he’d produced. Greene devised the plot, which had its origins in a single startling image he’d jotted down on the flap of an envelope: “I had paid my last farewell to Harry a week ago when his coffin was lowered into the frozen February ground, so that it was with incredulity that I saw him pass by without sign of recognition, among the host of strangers in the Strand.” Korda’s co-producer David Selznick provided money, the prospect of wide distribution in America, two stars from his own stable (Alida Valli and Joseph Cotten, who came to represent the soul of a surviving Europe and a dangerously innocent America), and an anti-Soviet undercurrent that Reed and Greene quietly buried, at least in the British version.

Reed used the time, while waiting for Welles to show up, to experiment with tilted cameras and surreal shadows

Then there’s Orson Welles as Harry Lime, leader of the gang peddling adulterated penicillin in Vienna. He dominates the film both by his presence and his absence. He was difficult to pin down, even for his brief appearances. Reed used the time shooting at night, while waiting for Welles to show up, to experiment with tilted cameras and surreal shadows in narrow, gleaming nocturnal streets that became one of the film’s hallmarks.

In 1979, during a BBC radio programme to mark Greene’s 75th birthday, I asked him which film based on his work had given him the greatest satisfaction. I expected him to say The Third Man. Instead he named The Fallen Idol, going on to explain that The Third Man was a director’s film, while The Fallen Idol was a writer’s picture. One can understand why, even while disagreeing with him. It was Carol Reed who was immediately fascinated on hearing Karas play the zither in a Viennese cafe and decided to bring the musician to London and settle for this single instrument. It was also Reed who decided to drop Greene’s original ending of a reconciliation between Holly Martins and Anna and opt for the bleak conclusion that the author thought audiences would find boring as they reached for hats under their seats. Reed also decided that there would be no subtitles to translate the German dialogue that Cotten’s Martins couldn’t understand: like him the audience would have to work out what people were saying.

There is perhaps another reason why Greene might have had certain reservations about The Third Man. Every time you see the film over the years you notice something new. You suddenly become aware, for instance, of the way the strings of the zither at the beginning are later echoed in the cables of the suspension bridge seen from above in the sequence in which the conspirators meet with Lime on the Danube, and later the wires of the Great Wheel in the Prater pleasure park, where Lime and Martins are to have their crucial meeting looking down on the world. Great spiders’ webs, perhaps, or the strings of giant marionettes?

Greene, despite the similarities between their works, had a loathing for Hitchcock’s films. But one notices the influence of The 39 Steps on the confrontation between Martins and Lime’s henchmen at the British Council lecture, and one also learns from Greene’s screenplay that the character of Crabbin (the cultural bureaucrat played by Wilfrid Hyde White) was originally written for Basil Radford and Naunton Wayne in the Charters and Caldicott personae created for Hitchcock’s The Lady Vanishes.

But the most striking influence that occurred to me only decades after first seeing The Third Man is its likely debt to Eric Ambler’s The Mask of Dimitrios, which turns upon a British thriller writer journeying to Istanbul to see a brilliant criminal who has disappeared after faking his death. There are several apparent allusions to Ambler’s book in the film (including one by Ambler’s friend, Carol Reed, to prewar Istanbul in the film’s stage-setting introduction), and Greene includes a chapter from The Mask of Dimitrios in his anthology, The Spies Bedside Book. During an onstage interview with Ambler at the National Film Theatre in he 1990s, I asked him if he’d ever noticed the resemblance. “I have indeed,” he replied, but sadly I never got around to pursuing the matter, and Ambler died soon afterwards.

The Germans have a term for movies set among the ruins of postwar cities – “Trümmerfilm” or “rubble films”. Notable in this sub-genre are such pictures of the 1940s as The Murderers Are Among Us (Wolfgang Staudte, 1946) and Germany Year Zero (Roberto Rossellini, 1948). The Third Man, deeply influenced by Italian neorealism, is arguably the most significant British example, though it has a close contender in Reed’s Odd Man Out (1947), shot on blitzed sites in Belfast, and Charles Crichton’s seminal Ealing comedy Hue and Cry (1947). Ken Adam, production designer on the early Bond movies, cut his teeth working on rubble films such as Obsession (1949) and Ten Seconds to Hell (1959) - (Phillip French, The Guardian).

Further Reading: https://cinephiliabeyond.org/t...

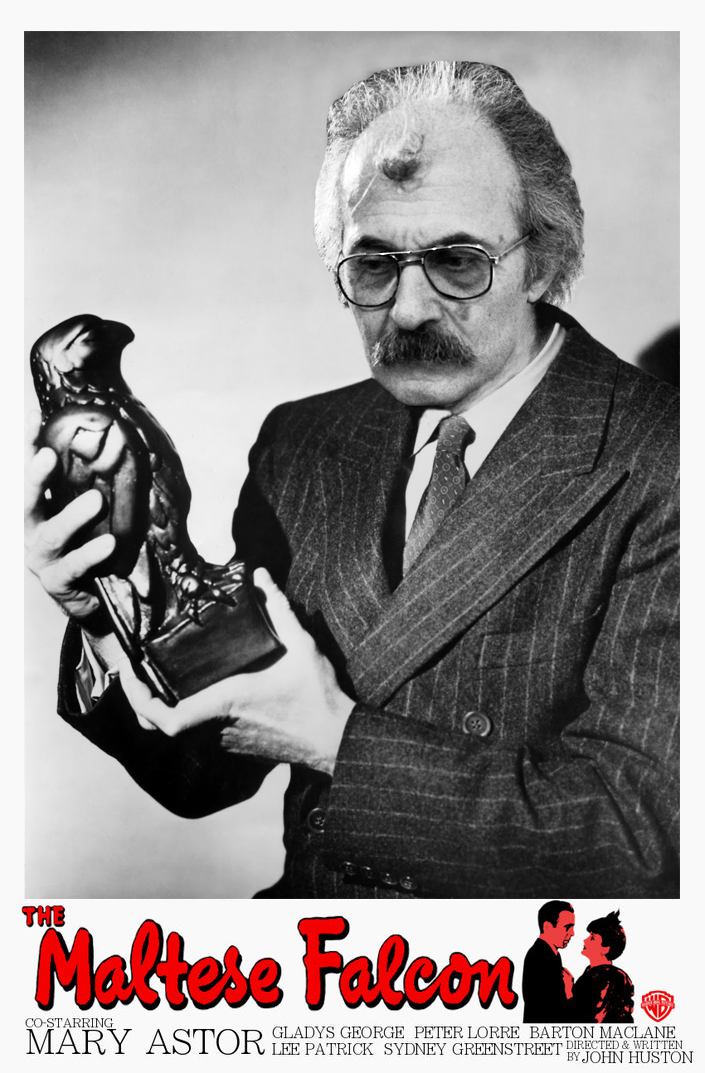

THE MALTESE FALCON (1941)

Among the movies we not only love but treasure, “The Maltese Falcon” stands as a great divide. Consider what was true after its release in 1941 and was not true before:

(1) The movie defined Humphrey Bogart's performances for the rest of his life; his hard-boiled Sam Spade rescued him from a decade of middling roles in B gangster movies and positioned him for “Casablanca,” “Treasure of the Sierra Madre,” “The African Queen” and his other classics.

(2) It was the first film directed by John Huston, who for more than 40 years would be a prolific maker of movies that were muscular, stylish and daring.

(3) It contained the first screen appearance of Sydney Greenstreet, who went on, in “Casablanca” and many other films, to become one of the most striking character actors in movie history.

(4) It was the first pairing of Greenstreet and Peter Lorre, and so well did they work together that they made nine other movies, including “Casablanca” in 1942 and “The Mask of Dimitrios” (1944), in which they were not supporting actors but actually the stars.

(5) And some film histories consider “The Maltese Falcon” the first film noir. It put down the foundations for that native American genre of mean streets, knife-edged heroes, dark shadows and tough dames.

Of course film noir was waiting to be born. It was already there in the novels of Dashiell Hammett, who wrote The Maltese Falcon, and the work of Raymond Chandler, James M. Cain, John O'Hara and the other boys in the back room. “Down these mean streets a man must go who is not himself mean,” wrote Chandler, and that was true of his hero Philip Marlowe (another Bogart character). But it wasn't true of Hammett's Sam Spade, whowas mean, and who set the stage for a decade in which unsentimental heroes talked tough and cracked wise.

The moment everyone remembers from “The Maltese Falcon” comes near the end, when Brigid O'Shaughnessy (Mary Astor) has been collared for murdering Spade's partner. She says she loves Spade. She asks if Sam loves her. She pleads for him to spare her from the law. And he replies, in a speech some people can quote by heart, “I hope they don't hang you, precious, by that sweet neck. . . . The chances are you'll get off with life. That means if you're a good girl, you'll be out in 20 years. I'll be waiting for you. If they hang you, I'll always remember you.”

Cold. Spade is cold and hard, like his name. When he gets the news that his partner has been murdered, he doesn't blink an eye. Didn't like the guy. Kisses his widow the moment they're alone together. Beats up Joel Cairo (Lorre) not just because he has to, but because he carries a perfumed handkerchief, and you know what that meant in a 1941 movie. Turns the rough stuff on and off. Loses patience with Greenstreet, throws his cigar into the fire, smashes his glass, barks out a threat, slams the door and then grins to himself in the hallway, amused by his own act.

If he didn't like his partner, Spade nevertheless observes a sort of code involving his death. “When a man's partner is killed,” he tells Brigid, “he's supposed to do something about it.” He doesn't like the cops, either; the only person he really seems to like is his secretary, Effie (Lee Patrick), who sits on his desk, lights his cigarettes, knows his sins and accepts them. How do Bogart and Huston get away with making such a dark guy the hero of a film? Because he does his job according to the rules he lives by, and because we sense (as we always would with Bogart after this role) that the toughness conceals old wounds and broken dreams.

John Huston had worked as a writer at Warner Bros. before convincing the studio to let him direct. “The Maltese Falcon” was his first choice, even though it had been filmed twice before by Warners (in 1931 under the same title and in 1936 as “Satan Met a Lady”). “They were such wretched pictures,” Huston told his biographer, Lawrence Grobel. He saw Hammett's vision more clearly, saw that the story was not about plot but about character, saw that to soften Sam Spade would be deadly, fought the tendency (even then) for the studio to pine for a happy ending.

When he finished his screenplay, he set to work story-boarding it, sketching every shot. That was the famous method of Alfred Hitchcock, whose “Rebecca” won the Oscar as the best picture of 1940. Like Orson Welles, who was directing “Citizen Kane” across town, Huston was excited by new stylistic possibilities; he gave great thought to composition and camera movement. To view the film in a stop-action analysis, as I have, is to appreciate complex shots that work so well they seem simple. Huston and his cinematographer, Arthur Edeson, accomplished things that in their way were as impressive as what Welles and Gregg Toland were doing on “Kane.”

Consider an astonishing unbroken seven-minute take. Grobel's bookThe Hustonsquotes Meta Wilde, Huston's longtime script supervisor: “It was an incredible camera setup. We rehearsed two days. The camera followed Greenstreet and Bogart from one room into another, then down a long hallway and finally into a living room; there the camera moved up and down in what is referred to as a boom-up and boom-down shot, then panned from left to right and back to Bogart's drunken face; the next pan shot was to Greenstreet's massive stomach from Bogart's point of view. . . . One miss and we had to begin all over again.”

Was the shot just a stunt? Not at all; most viewers don't notice it because they're swept along by its flow. And consider another shot, where Greenstreet chatters about the falcon while waiting for a drugged drink to knock out Bogart. Huston's strategy is crafty. Earlier, Greenstreet has set it up by making a point: “I distrust a man who says 'when.' If he's got to be careful not to drink too much, it's because he's not to be trusted when he does.” Now he offers Bogart a drink, but Bogart doesn't sip from it. Greenstreet talks on, and tops up Bogart's glass. He still doesn't drink. Greenstreet watches him narrowly. They discuss the value of the missing black bird. Finally, Bogart drinks, and passes out. The timing is everything; Huston doesn't give us closeups of the glass to underline the possibility that it's drugged. He depends on the situation to generate the suspicion in our minds. (This was, by the way, Greenstreet's first scene in the movies.)

The plot is the last thing you think of about “The Maltese Falcon.” The black bird (said to be made of gold and encrusted with jewels) has been stolen, men have been killed for it, and now Gutman (Greenstreet) has arrived with his lackeys (Lorre and Elisha Cook Jr.) to get it back. Spade gets involved because the Mary Astor character hires him to--but the plot goes around and around, and eventually we realize that the black bird is an example of Hitchcock's “MacGuffin”--it doesn't matter what it is, so long as everyone in the story wants or fears it.

To describe the plot in a linear and logical fashion is almost impossible. That doesn't matter. The movie is essentially a series of conversations punctuated by brief, violent interludes. It's all style. It isn't violence or chases, but the way the actors look, move, speak and embody their characters. Under the style is attitude: Hard men, in a hard season, in a society emerging from Depression and heading for war, are motivated by greed and capable of murder. For an hourly fee, Sam Spade will negotiate this terrain. Everything there is to know about Sam Spade is contained in the scene where Bridget asks for his help and he criticizes her performance: “You're good. It's chiefly your eyes, I think--and that throb you get in your voice when you say things like, 'be generous, Mr. Spade.' “ He always stands outside, sizing things up. Few Hollywood heroes before 1941 kept such a distance from the conventional pieties of the plot. (Roger Ebert)

Watch this wonderful talk by Adrien Wotton, OBE, CEO of Film London, about the making of the film: TALK

TO JOIN OUR MAILING LIST EMAIL US AT: info@cine-real.com

FOLLOW US ON INSTAGRAM: cinereal16mm