PAST SCREENINGS

Some Like it Hot

What a work of art and nature is Marilyn Monroe. She hasn't aged into an icon, some citizen of the past, but still seems to be inventing herself as we watch her. She has the gift of appearing to hit on her lines of dialogue by happy inspiration, and there are passages in Billy Wilder's "Some Like It Hot" where she and Tony Curtis exchange one-liners like hot potatoes.

Poured into a dress that offers her breasts like jolly treats for needy boys, she seems totally oblivious to sex while at the same time melting men into helpless desire. "Look at that!" Jack Lemmon tells Curtis as he watches her adoringly. "Look how she moves. Like Jell-O on springs. She must have some sort of built-in motor. I tell you, it's a whole different sex."

Wilder's 1959 comedy is one of the enduring treasures of the movies, a film of inspiration and meticulous craft, a movie that's about nothing but sex and yet pretends it's about crime and greed. It is underwired with Wilder's cheerful cynicism, so that no time is lost to soppiness and everyone behaves according to basic Darwinian drives. When sincere emotion strikes these characters, it blindsides them: Curtis thinks he wants only sex, Monroe thinks she wants only money, and they are as astonished as delighted to find they want only each other.

The plot is classic screwball. Curtis and Lemmon play Chicago musicians who disguise themselves as women to avoid being rubbed out after they witness the St. Valentine's Day Massacre. They join an all-girl orchestra on its way to Florida. Monroe is the singer, who dreams of marrying a millionaire but despairs, "I always get the fuzzy end of the lollipop." Curtis lusts for Monroe and disguises himself as a millionaire to win her. Monroe lusts after money and gives him lessons in love. Their relationship is flipped and mirrored in low comedy as Lemmon gets engaged to a real millionaire, played by Joe E. Brown. "You're not a girl!" Curtis protests to Lemmon. "You're a guy! Why would a guy want to marry a guy?" Lemmon: "Security!"

The movie has been compared to Marx Brothers classics, especially in the slapstick chases as gangsters pursue the heroes through hotel corridors. The weak points in many Marx Brothers films are the musical interludes--not Harpo's solos, but the romantic duets involving insipid supporting characters. "Some Like It Hot" has no problems with its musical numbers because the singer is Monroe, who didn't have a great singing voice but was as good as Frank Sinatra at selling the lyrics.

Consider her solo of "I Wanna Be Loved by You." The situation is as basic as it can be: a pretty girl standing in front of an orchestra and singing a song. Monroe and Wilder turn it into one of the most mesmerizing and blatantly sexual scenes in the movies. She wears that clinging, see-through dress, gauze covering the upper slopes of her breasts, the neckline scooping to a censor's eyebrow north of trouble. Wilder places her in the center of a round spotlight that does not simply illuminate her from the waist up, as an ordinary spotlight would, but toys with her like a surrogate neckline, dipping and clinging as Monroe moves her body higher and lower in the light with teasing precision. It is a striptease in which nudity would have been superfluous. All the time she seems unaware of the effect, singing the song innocently, as if she thinks it's the literal truth. To experience that scene is to understand why no other actor, male or female, has more sexual chemistry with the camera than Monroe.

Capturing the chemistry was not all that simple. Legends surround "Some Like It Hot." Kissing Marilyn, Curtis famously said, was like kissing Hitler. Monroe had so much trouble saying one line ("Where's the bourbon?") while looking in a dresser drawer that Wilder had the line pasted inside the drawer. Then she opened the wrong drawer. So he had it pasted inside every drawer.

Monroe's eccentricities and neuroses on sets became notorious, but studios put up with her long after any other actress would have been blackballed because what they got back on the screen was magical. Watch the final take of "Where's the bourbon?" and Monroe seems utterly spontaneous. And watch the famous scene aboard the yacht, where Curtis complains that no woman can arouse him, and Marilyn does her best. She kisses him not erotically but tenderly, sweetly, as if offering a gift and healing a wound. You remember what Curtis said but when you watch that scene, all you can think is that Hitler must have been a terrific kisser.

The movie is really the story of the Lemmon and Curtis characters, and it's got a top-shelf supporting cast (Joe E. Brown, George Raft, Pat O'Brien), but Monroe steals it, as she walked away with every movie she was in. It is an act of the will to watch anyone else while she is on the screen. Tony Curtis' performance is all the more admirable because we know how many takes she needed--Curtis must have felt at times like he was in a pro-am tournament. Yet he stays fresh and alive in sparkling dialogue scenes like their first meeting on the beach, where he introduces himself as the Shell Oil heir and wickedly parodies Cary Grant. Watch his timing in the yacht seduction scene, and the way his character plays with her naivete. "Water polo? Isn't that terribly dangerous?" asks Monroe. Curtis: "I'll say! I had two ponies drown under me."

Watch, too, for Wilder's knack of hiding bold sexual symbolism in plain view. When Monroe first kisses Curtis while they're both horizontal on the couch, notice how his patent-leather shoe rises phallically in the mid-distance behind her. Does Wilder intend this effect? Undoubtedly, because a little later, after the frigid millionaire confesses he has been cured, he says, "I've got a funny sensation in my toes--like someone was barbecuing them over a slow flame." Monroe's reply: "Let's throw another log on the fire."

Jack Lemmon gets the fuzzy end of the lollipop in the parallel relationship. The screenplay by Wilder and I.A.L. Diamond is Shakespearean in the way it cuts between high and low comedy, between the heroes and the clowns. The Curtis character is able to complete his round trip through gender, but Lemmon gets stuck halfway, so that Curtis connects with Monroe in the upstairs love story while Lemmon is downstairs in the screwball department with Joe E. Brown. Their romance is frankly cynical: Brown's character gets married and divorced the way other men date, and Lemmon plans to marry him for the alimony.

But they both have so much fun in their courtship! While Curtis and Monroe are on Brown's yacht, Lemmon and Brown are dancing with such perfect timing that a rose in Lemmon's teeth ends up in Brown's. Lemmon has a hilarious scene the morning after his big date, laying on his bed, still in drag, playing with castanets as he announces his engagement. (Curtis: "What are you going to do on your honeymoon?" Lemmon: "He wants to go to the Riviera, but I kinda lean toward Niagara Falls.") Both Curtis and Lemmon are practicing cruel deceptions--Curtis has Monroe thinking she's met a millionaire, and Brown thinks Lemmon is a woman--but the film dances free before anyone gets hurt. Both Monroe and Brown learn the truth and don't care, and after Lemmon reveals he's a man, Brown delivers the best curtain line in the movies. If you've seen the movie, you know what it is, and if you haven't, you deserve to hear it for the first time from him.

PATHS OF GLORY (1957) - NOV 2023

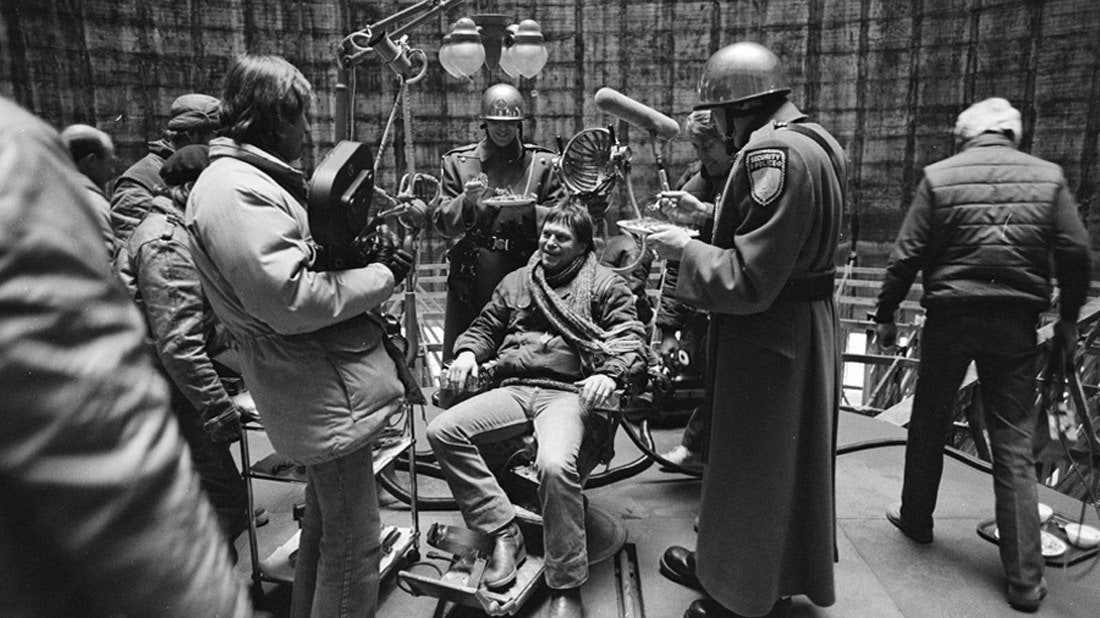

In 1945, a teenage Stanley Kubrick was given a job as staff photographer at Look magazine, where he published more than nine hundred striking images, most of them in the realist style of New York School street photography. By the end of the decade, he had taught himself to make movies, and with financial help from relatives, he became a pioneer of extremely low-budget, independent production. His first two features were the allegorical war picture Fear and Desire (1953) and the noir thriller Killer’s Kiss (1955), on both of which he served not only as producer and director but also as photographer, editor, and sound engineer. Then, in 1955, the preternaturally gifted Kubrick became a low-budget Hollywood director, joining forces with his contemporary the producer James B. Harris to make The Killing, a stylish heist film that was glowingly reviewed and much talked about within the industry but dumped into grind houses by its distributor, United Artists. His second film with Harris, a return to the theme of war, was even more impressive; Paths of Glory (1957), a scathing depiction of the murderous, face-saving machinations of an officer class, secured the young Kubrick’s reputation as a major talent.

The film originated when, on the strength of The Killing, Harris and Kubrick were briefly hired by MGM, where they proposed several projects that were rejected by the studio. Among these was an adaptation of Humphrey Cobb’s 1935 novel Paths of Glory, which Kubrick remembered having read in his father’s library as a teenager. Inspired by a New York Times story about five French soldiers in World War I who were executed by firing squad, the novel provided a harrowing account of trench warfare and an appalling picture of how generals treated their troops as cannon fodder. Playwright Sydney Howard had authored a Broadway adaptation in 1938, but by the mid-1950s, the book was virtually forgotten. Despite Kubrick’s enthusiasm, MGM turned the idea down, chiefly because it feared such a film would have difficulty getting distribution in Europe. Undeterred, Kubrick continued to develop a screenplay, aided by pulp novelist Jim Thompson, who had worked on The Killing, and playwright and novelist Calder Willingham, who had contributed to other unproduced Harris-Kubrick projects at MGM. This document ultimately came to the attention of a powerful and intelligent star: the muscular, dimple-chinned, intensely emotional Kirk Douglas, who was so impressed by it and by Kubrick’s work on The Killing that he offered to take the leading role and to pressure United Artists into financing the film under the auspices of his own company, Bryna Productions. With Douglas’s support, Paths of Glory went before the cameras on locations near Munich, Germany, budgeted at $1 million, more than a third of which went to the star. Harris and Kubrick agreed to work for a percentage of the profits, if profits ever came.

The completed film is strongly marked by what came to be known as Kubrick’s style and favored themes: a mesmerizing deployment of wide-angle tracking shots and long takes, an ability to make a realistic world seem strange, an interest in the grotesque, and a fascination with the underlying irrationality of supposedly rational planning. World War I was a particularly apt subject for Kubrick: generated by a meaningless tangle of nationalist alliances, it resulted in more than eight million military deaths, most caused by benighted politicians and generals who arranged massive bombardments and suicidal charges over open ground. Significantly, the concept of black humor, which is central to Kubrick’s work, was first articulated by the protosurrealist Jacques Vaché, a veteran of trench warfare in World War I, and yet of the several major films about the war, only Paths of Glory depicts the conflict in all its cruel, almost laughably absurd logic (All Quiet on the Western Front, Grand Illusion, The Dawn Patrol, and Sergeant York are humanistic, romantic, or patriotic by comparison). No wonder Luis Buñuel was among its passionate admirers.

To find anything similar to this attitude toward war, we need to consult Kubrick’s other films on the subject. In most cases, he underlines war’s absurdity by making the true conflict internecine and the ostensible enemy either semi-invisible or nearly indistinguishable from the story’s protagonists. In Fear and Desire, the paradigmatic instance, the same actors play both sides in a mysterious battle, as if the film were trying to illustrate a famous line from Walt Kelly’s Pogo: “We have met the enemy and he is us.” On the rare occasions when Kubrick’s soldiers have a close encounter with an Other from behind the lines, that person is either a doppelgänger or a woman. In Paths of Glory, the enemy is almost unseen, consisting mainly of lethal gunfire emanating from the smoke and darkness of no-man’s-land. The film differs from Kubrick’s normal pattern only in that, when French soldiers encounter a female German captive, she’s less an object of perverse desire and anxiety—as in Fear and Desire and Full Metal Jacket (1987)—than a maternal figure, producing a flood of repressed emotion and a momentary dissolution of psychic and bodily armor.

In one important way, however, Paths of Glory is quite atypical of Kubrick. Apart from Spartacus (1960), which also stars Kirk Douglas and over which Kubrick had relatively little control, it’s the only film he directed that has a protagonist with whom the audience can feel a straightforward, unproblematic identification. Colonel Dax, as portrayed by Douglas, is a loyal officer of a corrupt regime, but in most other ways he’s a paragon of heroic virtue. Handsome and brave, he takes the lead in a useless charge on the heavily fortified “Anthill,” picking his way through a withering storm of gunfire, crawling over casualties, and returning to the trench to try to rally reinforcements. Before the war, he happens also to have been “perhaps the foremost criminal lawyer in all of France.” When three enlisted men are arbitrarily selected to be executed for cowardice, he passionately and eloquently comes to their defense. After the executions, he denounces the general in charge in patented Douglas style, body and face contorted and voice pitched somewhere between a sob and a shout: “You’re a degenerate, sadistic old man and you can go to hell before I ever apologize to you again!”

Neither Cobb’s novel nor the theatrical adaptation by Howard is so much like a melodrama—a form Kubrick usually avoided but one basic to the liberal social-problem pictures in which Douglas was interested. Both earlier versions end abruptly with the executions (presented offstage in the play), and in neither does Dax lead a charge across no-man’s-land and serve as defense attorney at the court-martial. Cobb’s description of the attack on the German position, which he calls “the Pimple,” lacks even a trace of heroic spectacle. The film, on the other hand, is a star vehicle, giving Douglas the opportunity for derring-do. It even obeys the unwritten rule of most Kirk Douglas movies after his breakthrough role in Champion (1949): at some point, he will be seen without his shirt, as in his opening scene here, which has no equivalent in the novel or play.

At one stage, the screenplay was even more melodramatic. In his autobiography, Douglas says that when the production moved to Munich, Kubrick tried to reinstate the earlier version of the script by him and Thompson, which ended with a last-minute reprieve of the three condemned soldiers. Douglas flew into a rage and insisted on the version he had originally read. This contained revisions by Willingham, who, before his death in 1995, claimed that he was the author of “99 percent” of Paths of Glory. Actually, the final screenplay retains a good deal of Kubrick and Thompson, plus many important lines from Cobb’s novel. Thompson’s biographer, Robert Polito, shrewdly suggests that in momentarily proposing the other version, Kubrick may have been playing “ego chess” with Douglas, hoping to avoid further buildup of the star’s role. (In an unpublished 1962 interview with Terry Southern, Kubrick admitted there had been a discussion about reverting to the earlier screenplay—which, in addition to saving the three men, makes Dax a more ambiguous character—but denied that he ever seriously intended a happy ending: “There were some people who said you’ve got to save the men, but of course it was out of the question . . . It would just be pointless. Also, [the executions] really happened.”)

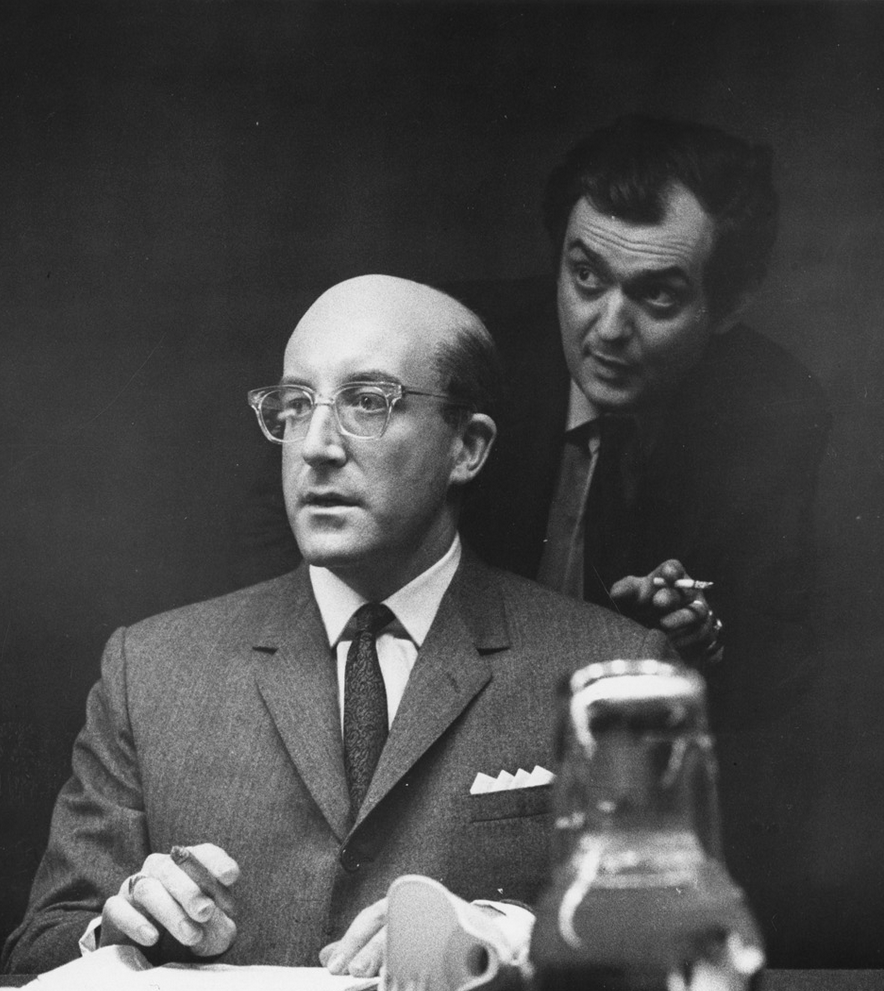

Whatever the case, there was a productive conflict between Douglas, who in print has called the director a “talented shit,” and Kubrick, whose lifelong motto might have been “silence, exile, and cunning.” Douglas was a flamboyant personality whose acting style and worldview lent themselves to melodramatic effects, whereas Kubrick was a dark, reclusive satirist who tended to parody or “quote” melodrama, as in such later films as Lolita (1962), Dr. Strangelove (1964), A Clockwork Orange (1972), and Barry Lyndon (1975). Between them, they fashioned a dark, emotionally disturbing film in which Douglas serves as the voice of reason and liberal humanism, tempering Kubrick’s harsh, traumatic view of European history.

The film received extraordinarily favorable reviews and gained Kubrick considerable cultural, if not financial, capital. (Unfortunately, MGM had been right about the European market. Paths of Glory was such a powerful indictment of military arrogance that the French government managed to have it dropped from the Berlin Film Festival and banned in France and Switzerland for two decades.) In a sense, Kubrick had won his battle for authorship, because what most people remember about the film is not so much the heroism of Colonel Dax as the grim photographic grisaille of trench warfare and the execution of three innocent men in the name of patriotic honor.

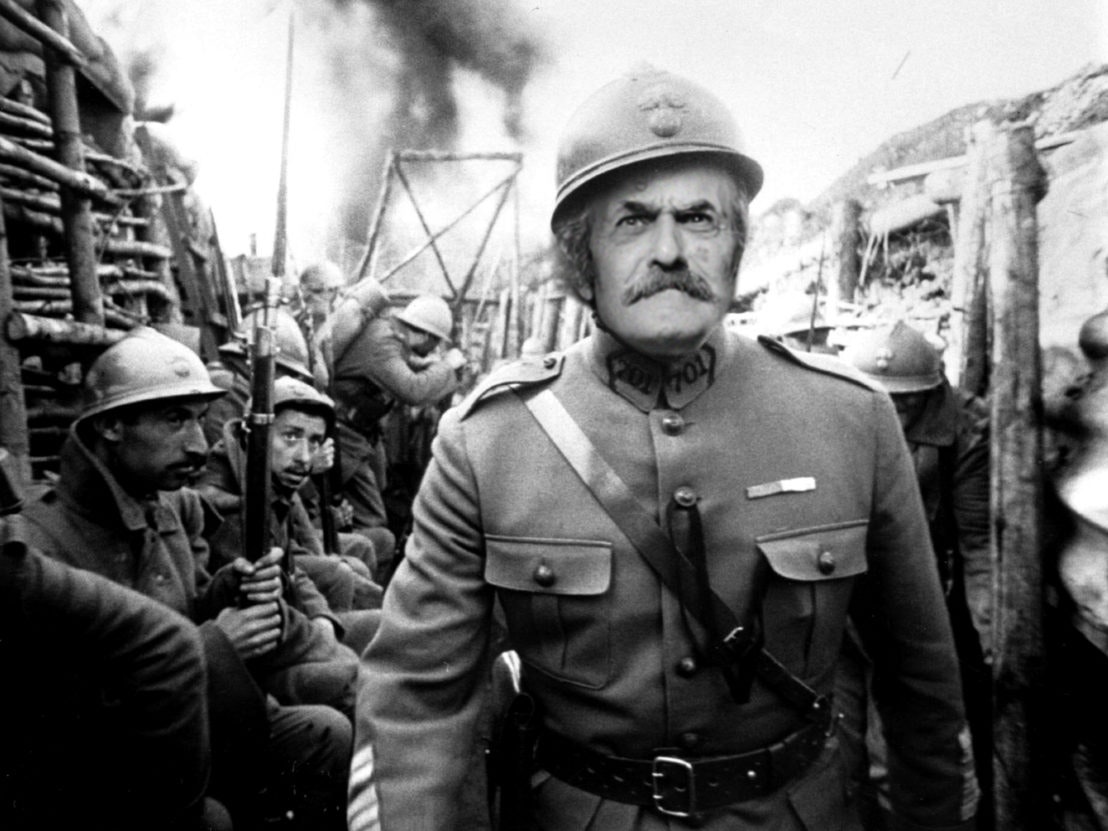

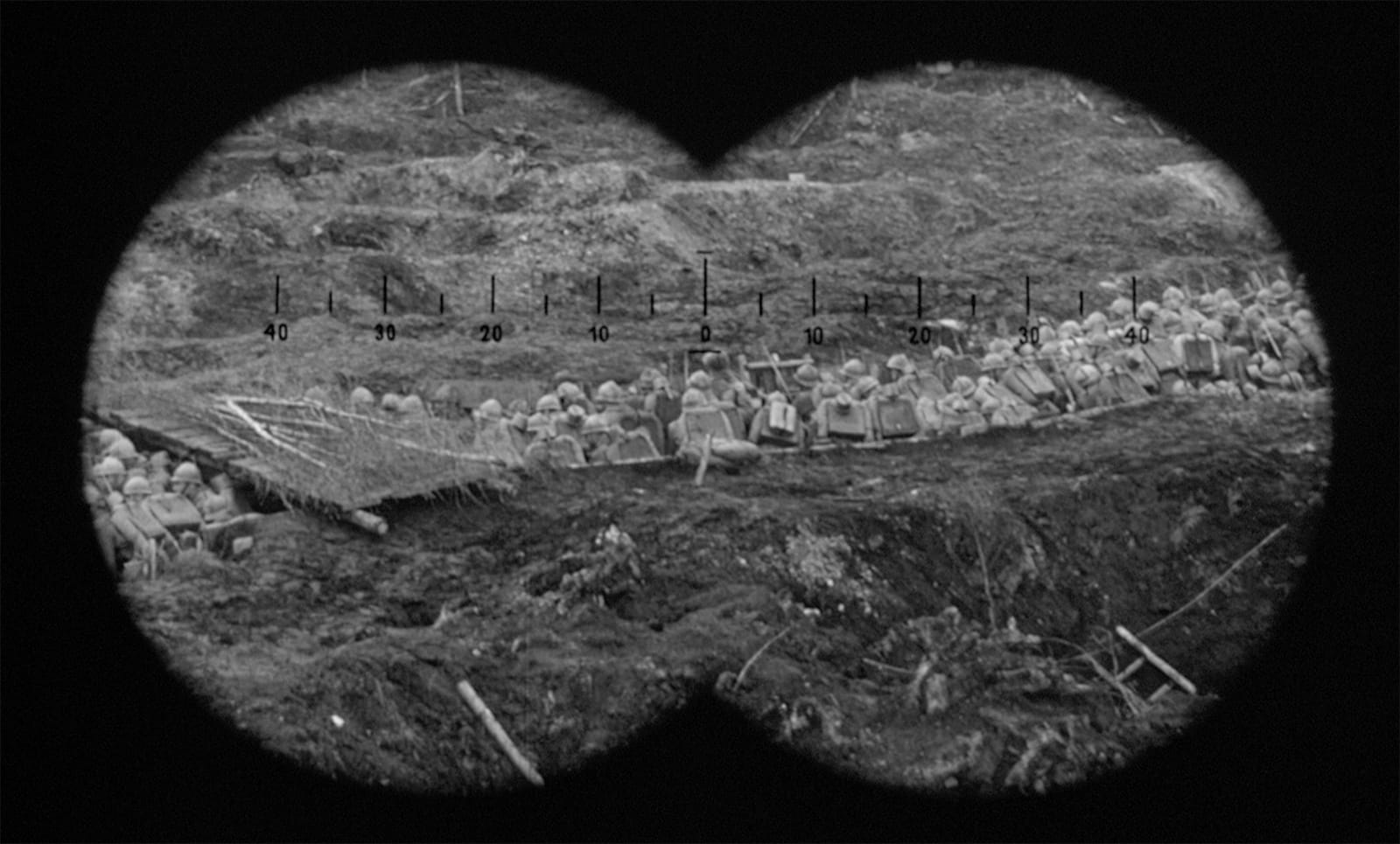

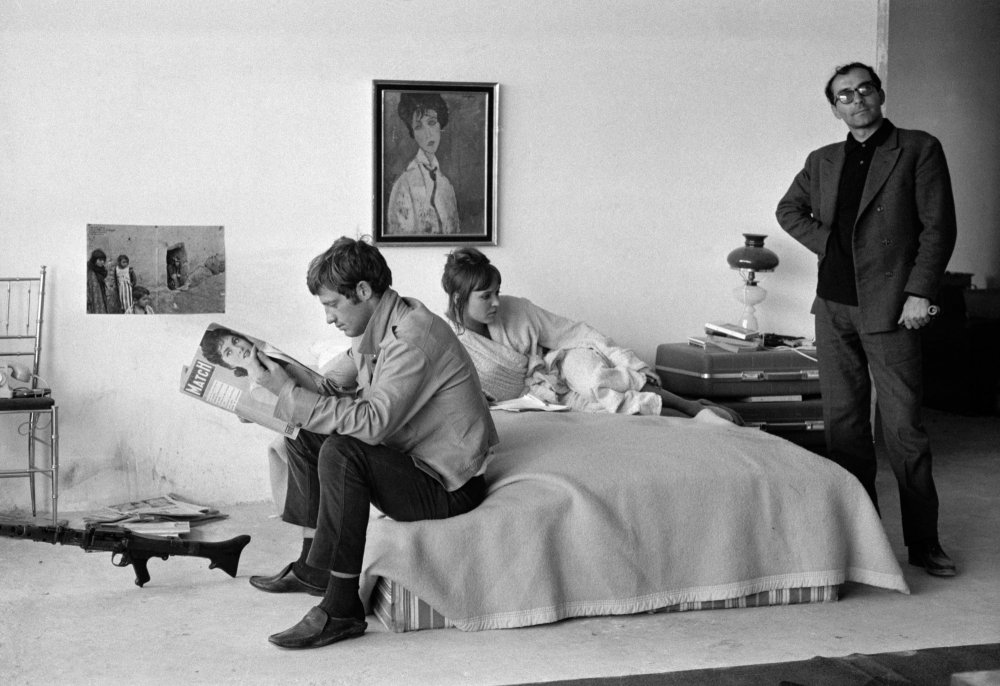

Kubrick is especially good at drawing sharp visual and aural contrasts between the château where the generals plan the war and the trenches where the war is fought. The Schleissheim Palace outside Munich, where much of the action takes place, later became a location for another film that depicts upper-class intrigues amid the architecture of a decadent past—Alain Resnais’ Last Year at Marienbad—and the opening sequence in the palace interior, where Adolphe Menjou suavely manipulates the ramrod stiff but insecure George Macready, was influenced by one of Kubrick’s favorite directors, Max Ophuls, who had died on the day it was staged. The camera dollies around a large room filled with artifacts of empire, engaging in a perversely Ophulsian choreography, while Kubrick, with the aid of cameraman George Krause, draws on his news photographer experience, making good use of natural light, deep-focus compositions, and sonic reverberations. In contrast, the trench warfare involves a signature Kubrick effect: wide-angle, almost phallic tracking shots down a sinister corridor or demonic tunnel. Dax’s march through the trench in preparation for an attack, lasting approximately two minutes and containing eight cuts, is an iconic moment for both the film and the director. Everything is in shades of gray, and the weary men along either side of the trench (played by a German police unit) have a sharply individuated, almost documentary authenticity. Dax walks grimly forward amid the rushing, high-pitched screams of inbound shells and earsplitting explosions that scatter shrapnel. In the penultimate shot, the camera, assuming his point of view, moves through a cloud of smoke in which only a few ghostly figures are visible, as if it were journeying into an underworld where the men are already dead.

The ceremony of execution, seen against the background of the château, gains impact from Kubrick’s deliberate pacing and dynamic manipulation of wide-angle perspectives. The camera advances slowly and inexorably toward the three stakes where the men are tied, and the elaborately drawn-out ritual, staged on a parade ground filled with military and civilian observers, looks obscenely overblown. The château looms like a confirmation of Walter Benjamin’s theory that every achievement of advanced civilization is also a monument to barbarism, but when the shooting happens, its ruthless efficiency and brutality are faced square on, with no picturesque embellishment.

After this horror, the audience is given a moment of relief when the German captive (Susanne Christian, who became Mrs. Stanley Kubrick) sings to a group of rowdy soldiers. The scene was written by Willingham over Kubrick’s initial objection, but its success has more to do with the director’s taste than with the writing. Kubrick avoids sentimentality by virtue of naturalistic lighting, nicely selected close-ups of nonprofessional faces, and skillful modulation from a mood of carnival to a mood of grief. The song, rendered in soft, amateurish fashion, is Frantzen-Gustav Gerdes’s “The Faithful Hussar,” which dates from the Napoleonic period. The French soldiers seem to understand the German lyrics, which end with “Oh please, Mother, bring a light, / My sweetheart is going to die” (my translation). Immediately afterward, Colonel Dax is informed that his troops have been ordered back into action. Gerald Fried’s nondiegetic music picks up Gerdes’s sweet melody, orchestrating it as a military march. The shattering film has offered only a brief nostalgic interlude before the barbaric system reasserts itself.

James Naremore, 2010

2001 (1968)

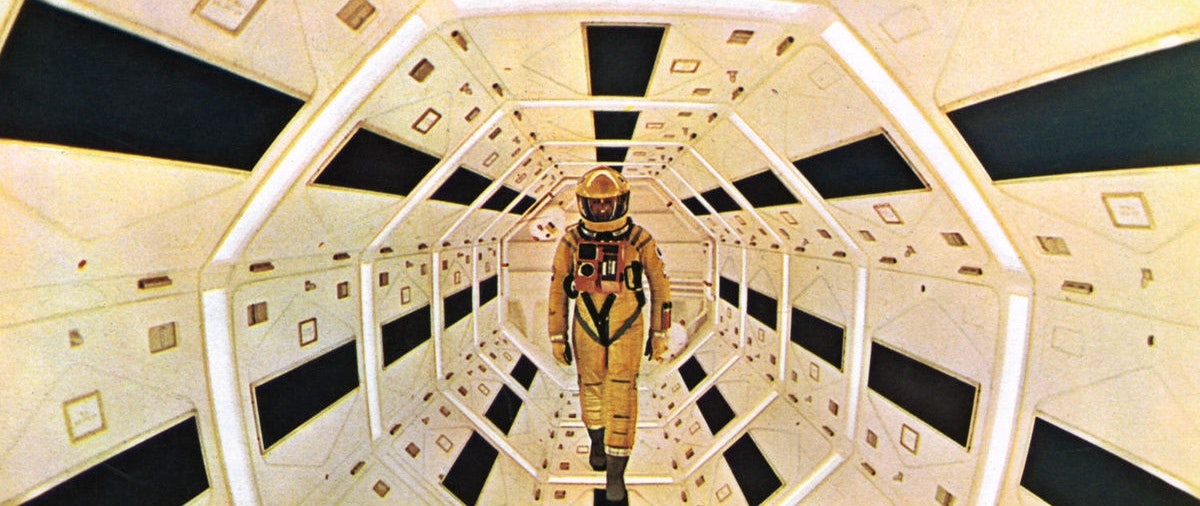

The genius is not in how much Stanley Kubrick does in "2001: A Space Odyssey," but in how little. This is the work of an artist so sublimely confident that he doesn't include a single shot simply to keep our attention. He reduces each scene to its essence, and leaves it on screen long enough for us to contemplate it, to inhabit it in our imaginations. Alone among science-fiction movies, “2001" is not concerned with thrilling us, but with inspiring our awe.

No little part of his effect comes from the music. Although Kubrick originally commissioned an original score from Alex North, he used classical recordings as a temporary track while editing the film, and they worked so well that he kept them. This was a crucial decision. North's score, which is available on a recording, is a good job of film composition, but would have been wrong for “2001" because, like all scores, it attempts to underline the action -- to give us emotional cues. The classical music chosen by Kubrick exists outside the action. It uplifts. It wants to be sublime; it brings a seriousness and transcendence to the visuals.

Consider two examples. The Johann Strauss waltz “Blue Danube,'' which accompanies the docking of the space shuttle and the space station, is deliberately slow, and so is the action. Obviously such a docking process would have to take place with extreme caution (as we now know from experience), but other directors might have found the space ballet too slow, and punched it up with thrilling music, which would have been wrong.

We are asked in the scene to contemplate the process, to stand in space and watch. We know the music. It proceeds as it must. And so, through a peculiar logic, the space hardware moves slowly because it's keeping the tempo of the waltz. At the same time, there is an exaltation in the music that helps us feel the majesty of the process.

Now consider Kubrick's famous use of Richard Strauss' “Thus Spake Zarathustra.'' Inspired by the words of Nietzsche, its five bold opening notes embody the ascension of man into spheres reserved for the gods. It is cold, frightening, magnificent.

The music is associated in the film with the first entry of man's consciousness into the universe - -and with the eventual passage of that consciousness onto a new level, symbolized by the Star Child at the end of the film. When classical music is associated with popular entertainment, the result is usually to trivialize it (who can listen to the “William Tell Overture'' without thinking of the Lone Ranger?). Kubrick's film is almost unique in enhancing the music by its association with his images.

I attended the Los Angeles premiere of the film, in 1968, at the Pantages Theater. It is impossible to describe the anticipation in the audience adequately. Kubrick had been working on the film in secrecy for some years, in collaboration, the audience knew, with author Arthur C. Clarke, special-effects expert Douglas Trumbull and consultants who advised him on the specific details of his imaginary future -- everything from space station design to corporate logos. Fearing to fly and facing a deadline, Kubrick had sailed from England on the Queen Elizabeth, doing the editing while on board, and had continued to edit the film during a cross-country train journey. Now it finally was ready to be seen.

To describe that first screening as a disaster would be wrong, for many of those who remained until the end knew they had seen one of the greatest films ever made. But not everyone remained. Rock Hudson stalked down the aisle, complaining, “Will someone tell me what the hell this is about?'' There were many other walkouts, and some restlessness at the film's slow pace (Kubrick immediately cut about 17 minutes, including a pod sequence that essentially repeated another one).

The film did not provide the clear narrative and easy entertainment cues the audience expected. The closing sequences, with the astronaut inexplicably finding himself in a bedroom somewhere beyond Jupiter, were baffling. The overnight Hollywood judgment was that Kubrick had become derailed, that in his obsession with effects and set pieces, he had failed to make a movie.

What he had actually done was make a philosophical statement about man's place in the universe, using images as those before him had used words, music or prayer. And he had made it in a way that invited us to contemplate it -- not to experience it vicariously as entertainment, as we might in a good conventional science-fiction film, but to stand outside it as a philosopher might, and think about it.

The film falls into several movements. In the first, prehistoric apes, confronted by a mysterious black monolith, teach themselves that bones can be used as weapons, and thus discover their first tools. I have always felt that the smooth artificial surfaces and right angles of the monolith, which was obviously made by intelligent beings, triggered the realization in an ape brain that intelligence could be used to shape the objects of the world.

The bone is thrown into the air and dissolves into a space shuttle (this has been called the longest flash-forward in the history of the cinema). We meet Dr. Heywood Floyd (William Sylvester), en route to a space station and the moon. This section is willfully anti-narrative; there are no breathless dialogue passages to tell us of his mission. Instead, Kubrick shows us the minutiae of the flight: the design of the cabin, the details of in-flight service, the effects of zero gravity.

Then comes the docking sequence, with its waltz, and for a time even the restless in the audience are silenced, I imagine, by the sheer wonder of the visuals. On board, we see familiar brand names, we participate in an enigmatic conference among the scientists of several nations, we see such gimmicks as a videophone and a zero-gravity toilet.

The sequence on the moon (which looks as real as the actual video of the moon landing a year later) is a variation on the film's opening sequence. Man is confronted with a monolith, just as the apes were, and is drawn to a similar conclusion: This must have been made. And as the first monolith led to the discovery of tools, so the second leads to the employment of man's most elaborate tool: the spaceship Discovery, employed by man in partnership with the artificial intelligence of the onboard computer, named HAL 9000.

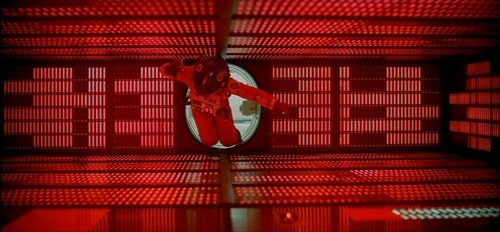

Life onboard the Discovery is presented as a long, eventless routine of exercise, maintenance checks and chess games with HAL. Only when the astronauts fear that HAL's programming has failed does a level of suspense emerge; their challenge is somehow to get around HAL, which has been programmed to believe, “This mission is too important for me to allow you to jeopardize it.'' Their efforts lead to one of the great shots in the cinema, as the men attempt to have a private conversation in a space pod, and HAL reads their lips. The way Kubrick edits this scene so that we can discover what HAL is doing is masterful in its restraint: He makes it clear, but doesn't insist on it. He trusts our intelligence.

Later comes the famous “star gate'' sequence, a sound and light journey in which astronaut Dave Bowman (Keir Dullea) travels through what we might now call a wormhole into another place, or dimension, that is unexplained. At journey's end is the comfortable bedroom suite in which he grows old, eating his meals quietly, napping, living the life (I imagine) of a zoo animal who has been placed in a familiar environment. And then the Star Child.

There is never an explanation of the other race that presumably left the monoliths and provided the star gate and the bedroom. “2001'' lore suggests Kubrick and Clarke tried and failed to create plausible aliens. It is just as well. The alien race exists more effectively in negative space: We react to its invisible presence more strongly than we possibly could to any actual representation.

“2001: A Space Odyssey'' is in many respects a silent film. There are few conversations that could not be handled with title cards. Much of the dialogue exists only to show people talking to one another, without much regard to content (this is true of the conference on the space station). Ironically, the dialogue containing the most feeling comes from HAL, as it pleads for its “life'' and sings “Daisy.''

The film creates its effects essentially out of visuals and music. It is meditative. It does not cater to us, but wants to inspire us, enlarge us. Nearly 30 years after it was made, it has not dated in any important detail, and although special effects have become more versatile in the computer age, Trumbull's work remains completely convincing -- more convincing, perhaps, than more sophisticated effects in later films, because it looks more plausible, more like documentary footage than like elements in a story.

Only a few films are transcendent, and work upon our minds and imaginations like music or prayer or a vast belittling landscape. Most movies are about characters with a goal in mind, who obtain it after difficulties either comic or dramatic. “2001: A Space Odyssey'' is not about a goal but about a quest, a need. It does not hook its effects on specific plot points, nor does it ask us to identify with Dave Bowman or any other character. It says to us: We became men when we learned to think. Our minds have given us the tools to understand where we live and who we are. Now it is time to move on to the next step, to know that we live not on a planet but among the stars, and that we are not flesh but intelligence.

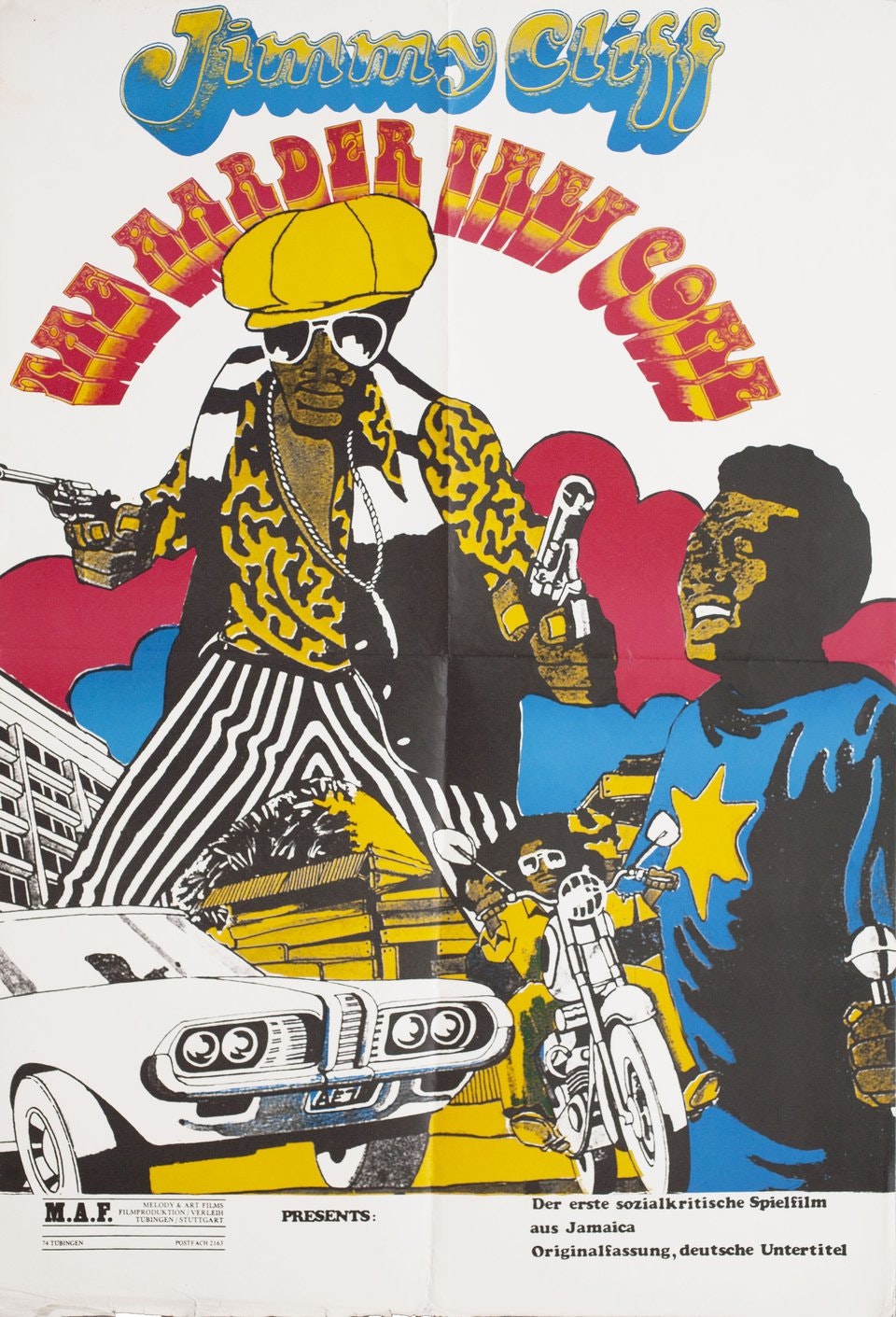

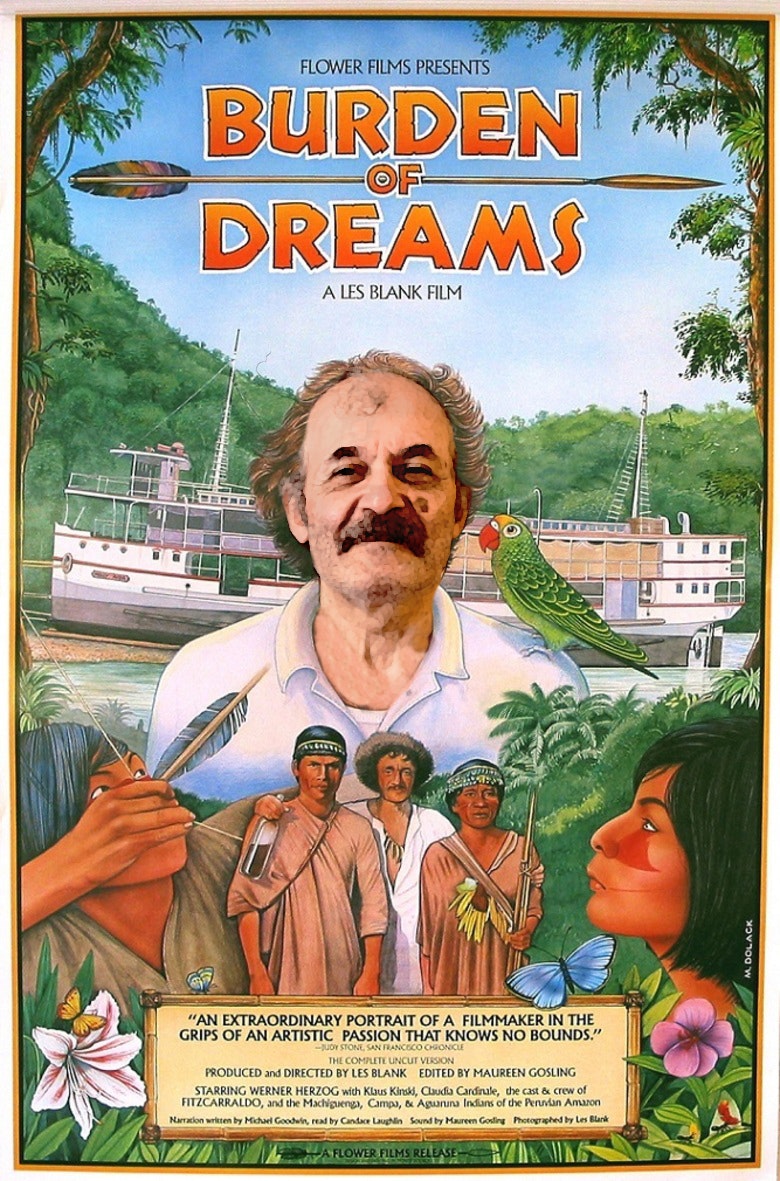

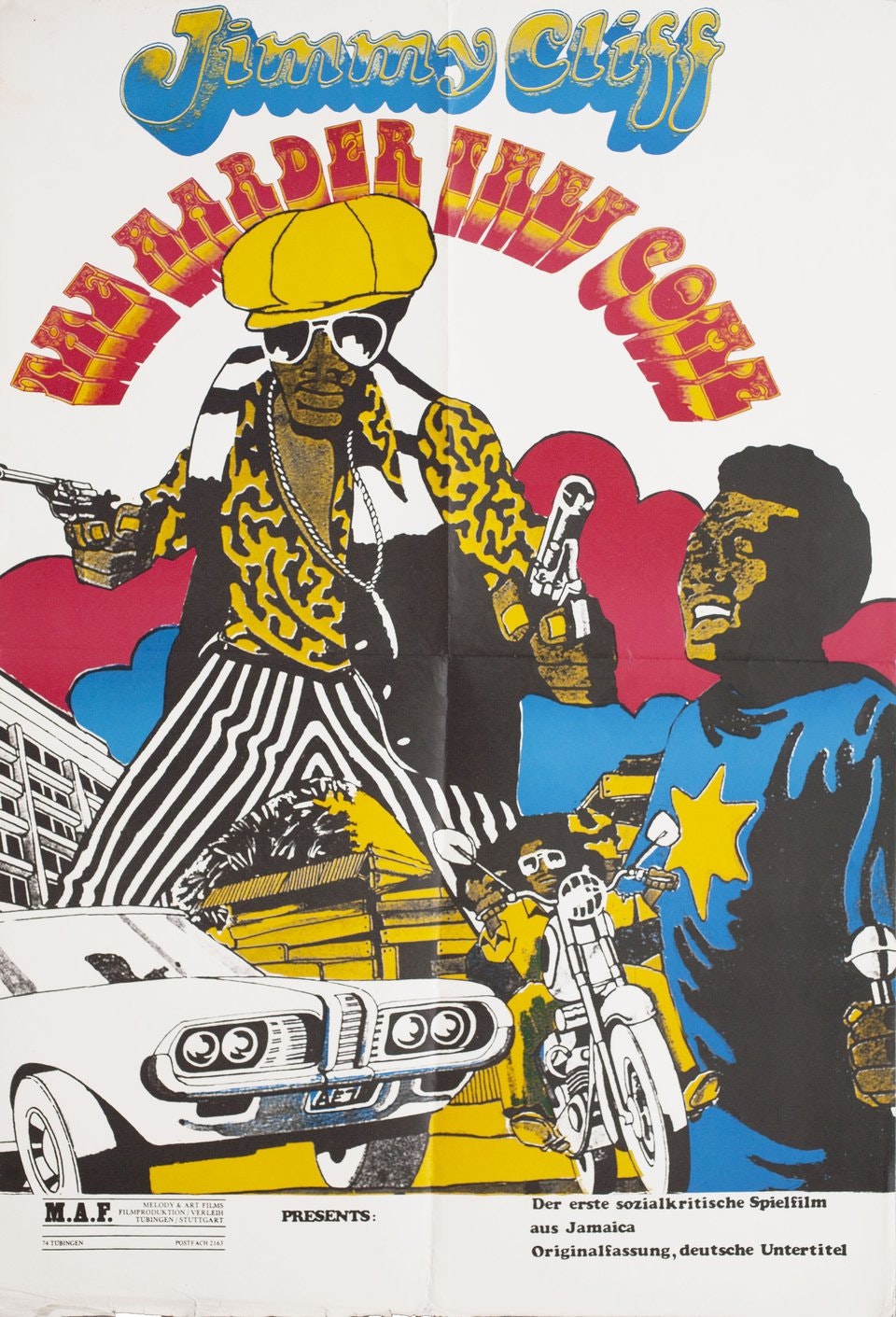

THE HARDER THEY COME (1972)

A brash bumpkin from the countryside comes to the city, dreaming of stardom. He cuts a record, gets ripped off, turns to trafficking drugs, is betrayed, and dies a folk hero at the hands of the police as his song becomes an anthem.

“The Harder They Come,” is a universal story set in a highly specific milieu. Powered by one of the most infectious scores in the history of cinema, it is also a pop classic — the movie that brought reggae to America and “launched a thousand spliffs,” as the New York Times critic Ben Brantley joked in a 2008 review of a theatrical version in London.

Inspired by the life of the Jamaican outlaw Ivanhoe “Rhygin” Martin, credited with the line that gives the movie its title, “The Harder They Come” was a vehicle for the reggae star Jimmy Cliff. It was independent Jamaica’s first homemade feature, as well as the first film directed by Perry Henzell, a scion of that nation’s white planter class. The distinguished black playwright Trevor Rhone co-wrote the script. (“The Harder They Come” is being shown in conjunction with the theatrical release of Henzell’s long-delayed follow-up, “No Place Like Home,” which is also at BAM.)

Beginner’s luck — or lack of same — might almost be the movie’s subject. Robbed upon arrival in Kingston, Ivan Martin (Cliff) founders at first in the urban maelstrom. Social conditions are manifest in documentary-type shots, filmed in 16 millimeter, of poverty and desperation. Ivan finds his footing only to mix it up with an assortment of predatory preachers, mercenary record producers, corrupt cops and miscellaneous hustlers. In the background, Toots & the Maytals, Desmond Dekker, Cliff and others sing a collective siren song of fame. Chased by the police, Ivan creates his own legend, leaving graffiti (“I am here — I am everywhere”) and imagining an audience for his last stand.

A movie of abrupt transitions, “The Harder They Come” appears to have been assembled piecemeal and shot off the cuff. Cliff, who wrote the title song, has described the film changing direction while in production. In an article published in The Caribbean Quarterly in 2015, the cinematographer Franklyn St. Juste said he never saw a script: “I really didn’t know what was happening — and what was going to happen from one scene to the next or from one setup to the next.” But the spontaneity proved a recipe for what St. Juste termed “happy accidents.”

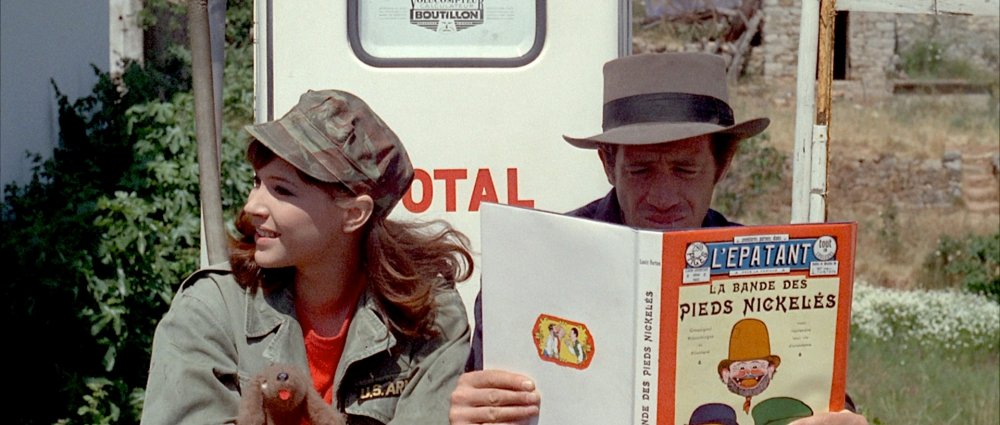

The timing was also fortuitous. The film arrived on the international scene in the wake of “Shaft” (1971) and “Superfly” (1972), with a hero akin to the righteous outlaws in films like the Brazilian director Glauber Rocha’s “Antonio das Mortes” (1969), Melvin Van Peebles’s “Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song” (1971) and numerous Italian westerns. (It’s hardly coincidental that Ivan goes to see “Django,” Sergio Corbucci’s 1966 evergreen.) For early audiences, Ivan’s willingness to defy authority at the cost of his life evoked Bonnie and Clyde, the Black Panthers and Che Guevara.

After making a splash at the 1972 Venice Film Festival, “The Harder They Come” was picked up by Roger Corman’s New World Pictures; it opened (with English subtitles, because of the particularly thick Jamaican patois) to some success at a Broadway theater in February 1973 and enjoyed a second run as an exploitation film. (I saw it that summer in Florida on a double bill with the Pam Grier prison movie “Black Mama, White Mama.”) It would soon have a third life. In a 1974 piece titled “Films That Refuse to Fade Away,” the New York Times critic Vincent Canby noted the movie’s popularity as a midnight attraction.

As reported by Canby, “The Harder They Come” ran for 26 weeks at the Orson Welles Cinema in Cambridge, Mass., in 1973. A true cult film, it was brought back in 1974, where, as Jonathan Rosenbaum and I wrote in our book “Midnight Movies,” it remained another seven years. In April 1976, The Times ran an article, noting that “The Harder They Come” had played 80 consecutive weekends at the Elgin Theater in Chelsea. (The run would continue there for months.)

That film’s director, Franco Rosso, named “The Harder They Come” as his inspiration. “Babylon” (1980) might be a sequel, focusing on West Indian life in London. An immersive, verité-style movie following a disaffected young singer of a homegrown reggae group, it uses a constant flow of music to animate the struggle for survival in a hostile white world. “The movie is more interested in what feels right than what seems right,” the critic Wesley Morris wrote in his review for The Times.In his enthusiasm, Canby called “The Harder They Come” “a more revolutionary black film than any number of American efforts, including ‘Sweet Sweetback’s Baadasssss Song.’” In any case, “The Harder They Come” provided a model for later movies, most notably the 1980 British film “Babylon,”

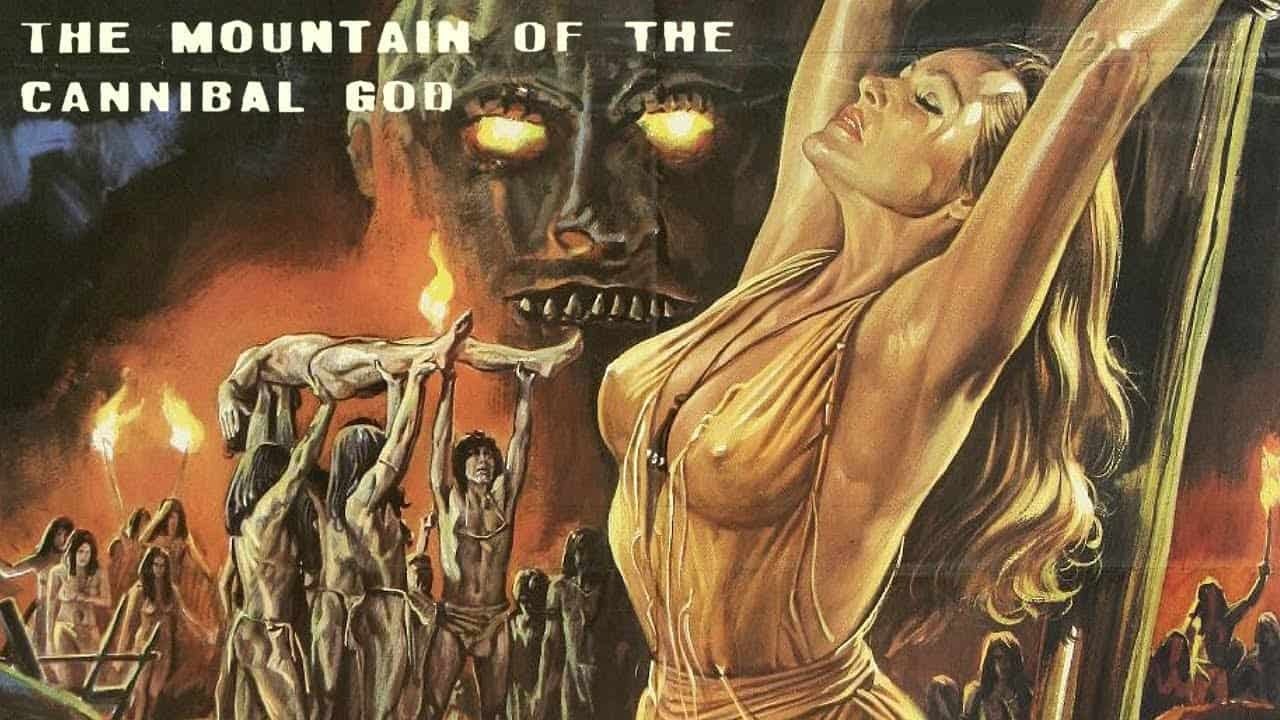

THE MOUNTAIN OF THE CANNIBAL GOD (AKA THE SLAVE OF THE CANNIBAL GOD) (1978)

he Mountain of The Cannibal God belongs to the Italian cannibal movie subgenre that briefly flourished during the late 70s and early 80’s, which still hold the power to shock – and repulse – like few horror flicks can. These movies typically feature a group of explorers setting off on a wacky adventure into the jungle, before running afoul of a native tribe that has unique plans for dinner. The ingredients of these movies involve stomach-churning gore, scenes of sexual violence and real-life animal cruelty, with Cannibal Holocaust considered the most powerful the genre has to offer.

So basically, they’re not really fluffy pizza and beer movies, though The Mountain Of The Cannibal God is probably one of the ‘lighter’ entries. The story kicks into gear when a rich wife (Ursula Andress) hires a tribal expert (Stacy Keach) to help her find her missing husband in the jungles of New Guinea. Andress and co descend ever deeper into hell, and in addition to surviving the jungle with its killer animals and harsh terrain, they find themselves under attack by a literal bloodthirsty tribe.

While The Mountain Of The Cannibal God is more of an adventure than other movies in the genre, that doesn’t mean it skimps on bloodshed. Heads – and other body parts – are hacked off with gusto, and the camera doesn’t shy away from the details when the dinner bell rings. The movie is also known for a few shots of unpleasant animal cruelty, such as a moment featuring a monkey being eaten by a snake.

Andress doesn’t make much of an impression in the lead role and mostly has the same reaction to everything, be it looking at a map or watching someone gets castrated. That said, her utter lack of dimension helps mask a good plot reveal. Thankfully Keach picks up the slack and is even borderline hunky as the expert who is haunted by a past experience with the tribe. The movie really builds to the reveal of the tribe too, and they’re pretty creepy when it keeps them in the shadows.

The Mountain Of The Cannibal God finds time to slip in plenty of sleaze too, with lingering shots of Andress getting oiled up by natives, or shots of masturbation and bestiality in the third act. The movie can be a touch grueling at times, but in terms of pace it rarely drags, and Sergio Martino does a solid job in the director’s chair.

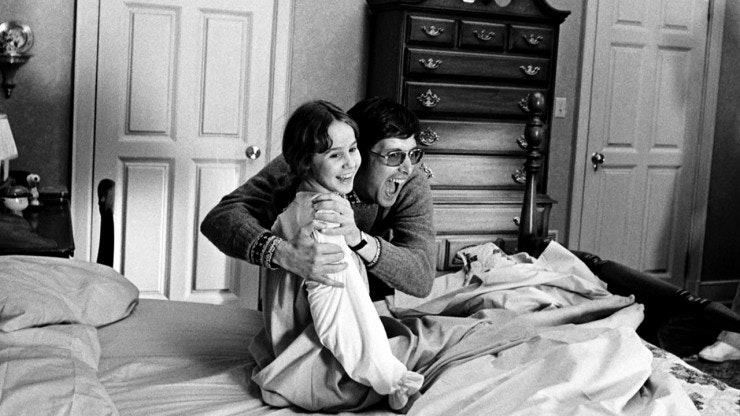

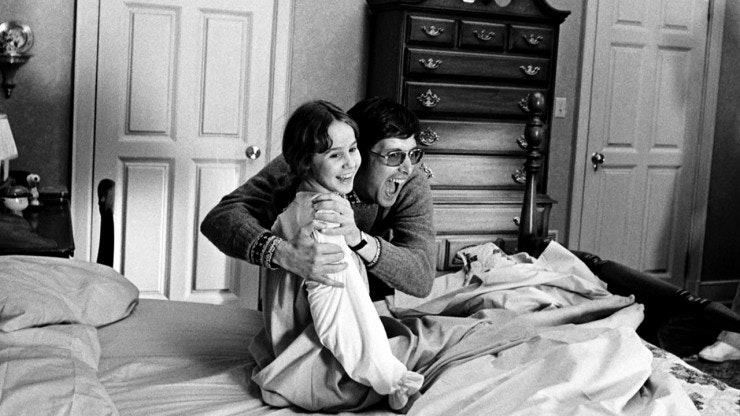

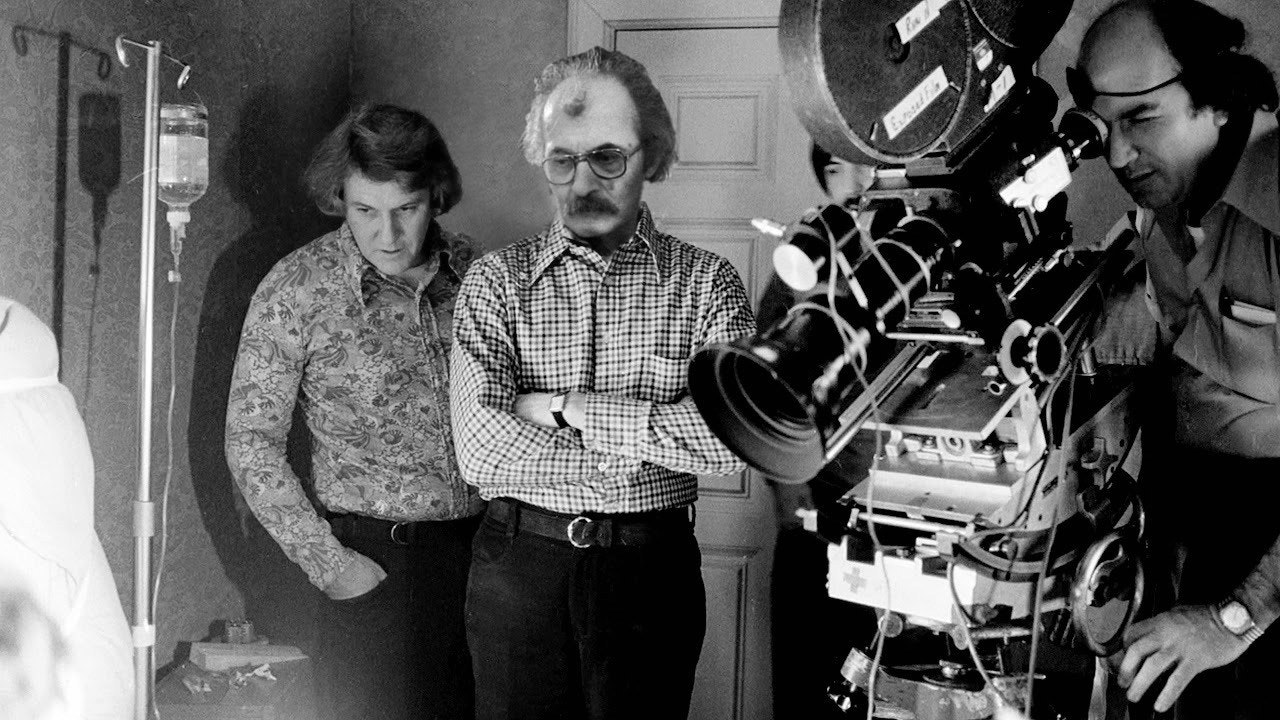

THE EXORCIST (1973)

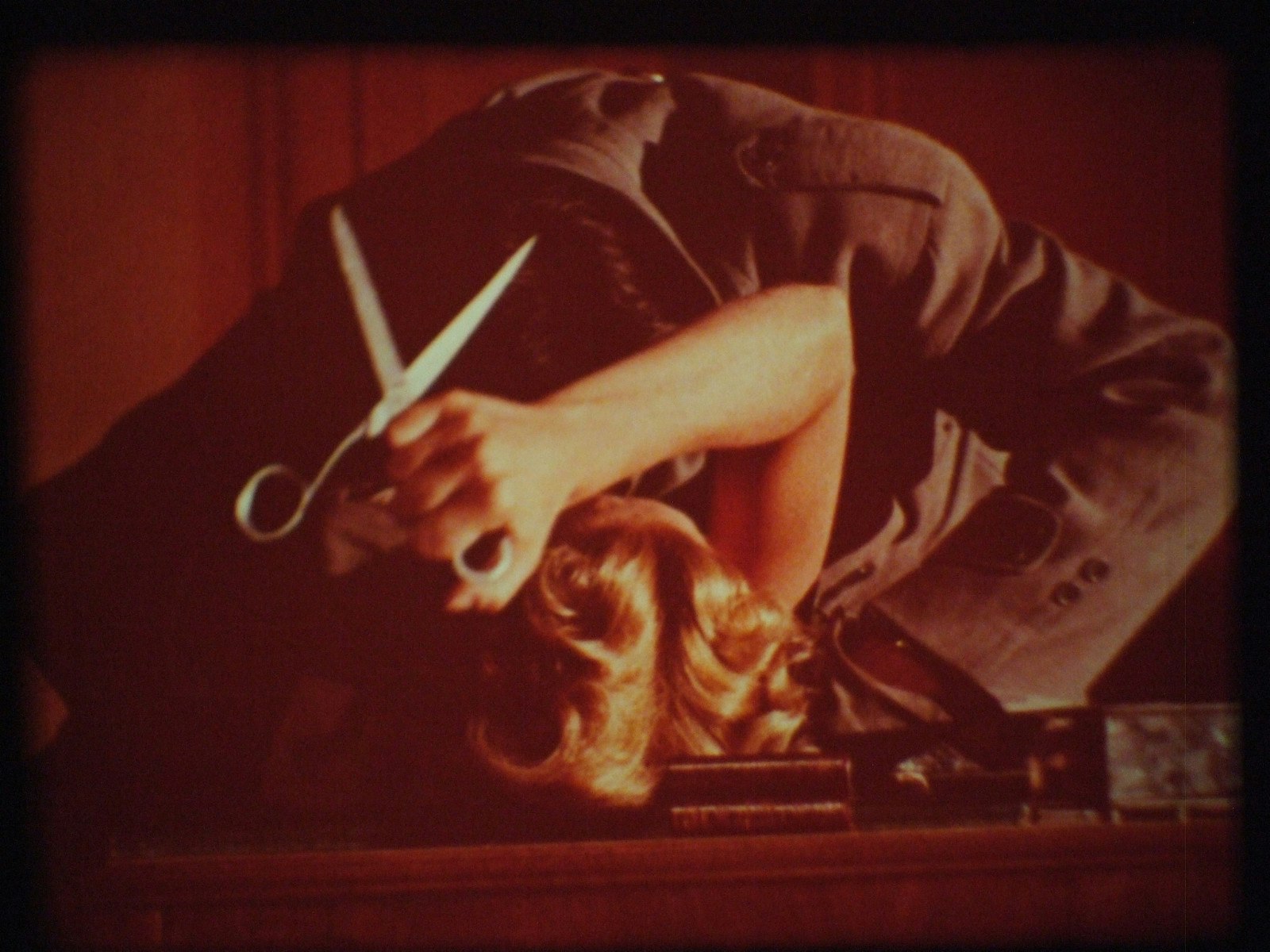

The year 1973 began and ended with cries of pain. It began with Ingmar Bergman’s “Cries and Whispers,” and it closed with William Friedkin’s “The Exorcist.” Both films are about the weather of the human soul, and no two films could be more different. Yet each in its own way forces us to look inside, to experience horror, to confront the reality of human suffering. The Bergman film is a humanist classic. The Friedkin film is an exploitation of the most fearsome resources of the cinema. That does not make it evil, but it does not make it noble, either.

The difference, maybe, is between great art and great craftsmanship. Bergman’s exploration of the lines of love and conflict within the family of a woman dying of cancer was a film that asked important questions about faith and death, and was not afraid to admit there might not be any answers. Friedkin’s film is about a twelve-year-old girl who either is suffering from a severe neurological disorder or perhaps has been possessed by an evil spirit. Friedkin has the answers; the problem is that we doubt he believes them.

We don’t necessarily believe them ourselves, but that hardly matters during the film’s two hours. If movies are, among other things, opportunities for escapism, then “The Exorcist” is one of the most powerful ever made. Our objections, our questions, occur in an intellectual context after the movie has ended. During the movie there are no reservations, but only experiences. We feel shock, horror, nausea, fear, and some small measure of dogged hope.

Rarely do movies affect us so deeply. The first time I saw “Cries and Whispers,” I found myself shrinking down in my seat, somehow trying to escape from the implications of Bergman’s story. “The Exorcist” also has that effect--but we’re not escaping from Friedkin’s implications, we’re shrinking back from the direct emotional experience he’s attacking us with. This movie doesn’t rest on the screen; it’s a frontal assault.

The story is well-known; it’s adapted, more or less faithfully, by William Peter Blatty from his own bestseller. Many of the technical and theological details in his book are accurate. Most accurate of all is the reluctance of his Jesuit hero, Father Karras, to encourage the ritual of exorcism: “To do that,” he says, “I’d have to send the girl back to the sixteenth century.” Modern medicine has replaced devils with paranoia and schizophrenia, he explains. Medicine may have, but the movie hasn’t. The last chapter of the novel never totally explained in detail the final events in the tortured girl’s bedroom, but the movie’s special effects in the closing scenes leave little doubt that an actual evil spirit was in that room, and that it transferred bodies. Is this fair? I guess so; in fiction the artist has poetic license.

It may be that the times we live in have prepared us for this movie. And Friedkin has admittedly given us a good one. I’ve always preferred a generic approach to film criticism; I ask myself how good a movie is of its type. “The Exorcist” is one of the best movies of its type ever made; it not only transcends the genre of terror, horror, and the supernatural, but it transcends such serious, ambitious efforts in the same direction as Roman Polanski’s “Rosemary’s Baby.” Carl Dreyer’s “The Passion of Joan of Arc” is a greater film--but, of course, not nearly so willing to exploit the ways film can manipulate feeling.

“The Exorcist” does that with a vengeance. The film is a triumph of special effects. Never for a moment--not when the little girl is possessed by the most disgusting of spirits, not when the bed is banging and the furniture flying and the vomit is welling out--are we less than convinced. The film contains brutal shocks, almost indescribable obscenities. That it received an R rating and not the X is stupefying.

The performances are in every way appropriate to this movie made this way. Ellen Burstyn, as the possessed girl’s mother, rings especially true; we feel her frustration when doctors and psychiatrists talk about lesions on the brain and she knows there’s something deeper, more terrible, going on. Linda Blair, as the little girl, has obviously been put through an ordeal in this role, and puts us through one. Jason Miller, as the young Jesuit, is tortured, doubting, intelligent.

And the casting of Max von Sydow as the older Jesuit exorcist was inevitable; he has been through so many religious and metaphysical crises in Bergman’s films that he almost seems to belong on a theological battlefield the way John Wayne belonged on a horse. There’s a striking image early in the film

that has the craggy von Sydow facing an ancient, evil statue; the image doesn’t so much borrow from Bergman’s famous chess game between von Sydow and Death (in “The Seventh Seal”) as extend the conflict and raise the odds.

I am not sure exactly what reasons people will have for seeing this movie; surely enjoyment won’t be one, because what we get here aren’t the delicious chills of a Vincent Price thriller, but raw and painful experience. Are people so numb they need movies of this intensity in order to feel anything at all? It’s hard to say.

Even in the extremes of Friedkin’s vision there is still a feeling that this is, after all, cinematic escapism and not a confrontation with real life. There is a fine line to be drawn there, and “The Exorcist” finds it and stays a millimeter on this side.

Get your tickets: HERE

TO JOIN OUR MAILING LIST EMAIL US AT:

EMAIL: info@cine-real.com

INSTAGRAM - cinereal16mm

The Loneliness of the Long Distance Runner (1962)

Though it never achieved quite the same level of accomplishment, or recognition, as its French counterpart, the British New Wave of the late Fifties and early Sixties nevertheless managed to produce a number of felicitious films, such as The Loneliness Of The Long Distance Runner.

Adapted for the screen by Alan Sillitoe from his own short story, the film relates the story of Colin Smith (Tom Courtenay), a rebellious and disaffected teenager, whose kicks against the pricks, along with some thievery, swiftly lead to borstal. There, his talent for cross country running is noticed - a talent which earns him both preferential treatment from the regime and the enmity of less favoured inmates.

Things come to a head when the governor (Michael Redgrave) has Colin enter a race against a group of local public schoolboys...

The British New Wave was always marked by apparent contradictions, not least the fact that predominantly public (ie, for the benefit of our American friends, private) school and Oxbridge educated filmmakers were seeking to make gritty and realistic - as the cliche invariably puts it - films about working-class life; a situation always likely to lead to touristic, impressionistic pieces that presented a world the director/auteur found a nice place to visit, but wouldn't want to live in.

Questions of class voyeurism aside, The Loneliness Of The Long Distance Runner works better than many of its peers, retaining its freshness and a degree of relevance 40 years on, thanks to the timeless, placeless main theme of rebellion-vs-conformity and the continuing fallout of debates over the influence of American/mass/consumer culture, as epitomised here by the villainous TV set (though oddly trad jazz - the subject of Richardson's earlier Free Cinema short, Momma Don't Allow - seems to be okay) on "the British way of life".

This said, Richardson displays a surprising affinity for the material, possibly the result of an insight that, be it boarding school, barrack room or borstal, Britain's "total institutions" - to use Irving Goffman's phrase - have always been much the same in terms of corrupt(ing) master/slave power relations.

But if anything contributes to its lasting influence, it's not all this political stuff, rather the brilliant performance by Tom Courtenay - all the more remarkable given his youth and inexperience in what was his film debut - and the beautiful, alternately poetic and documentary realist black-and-white, cinematography by Walter Lassally.

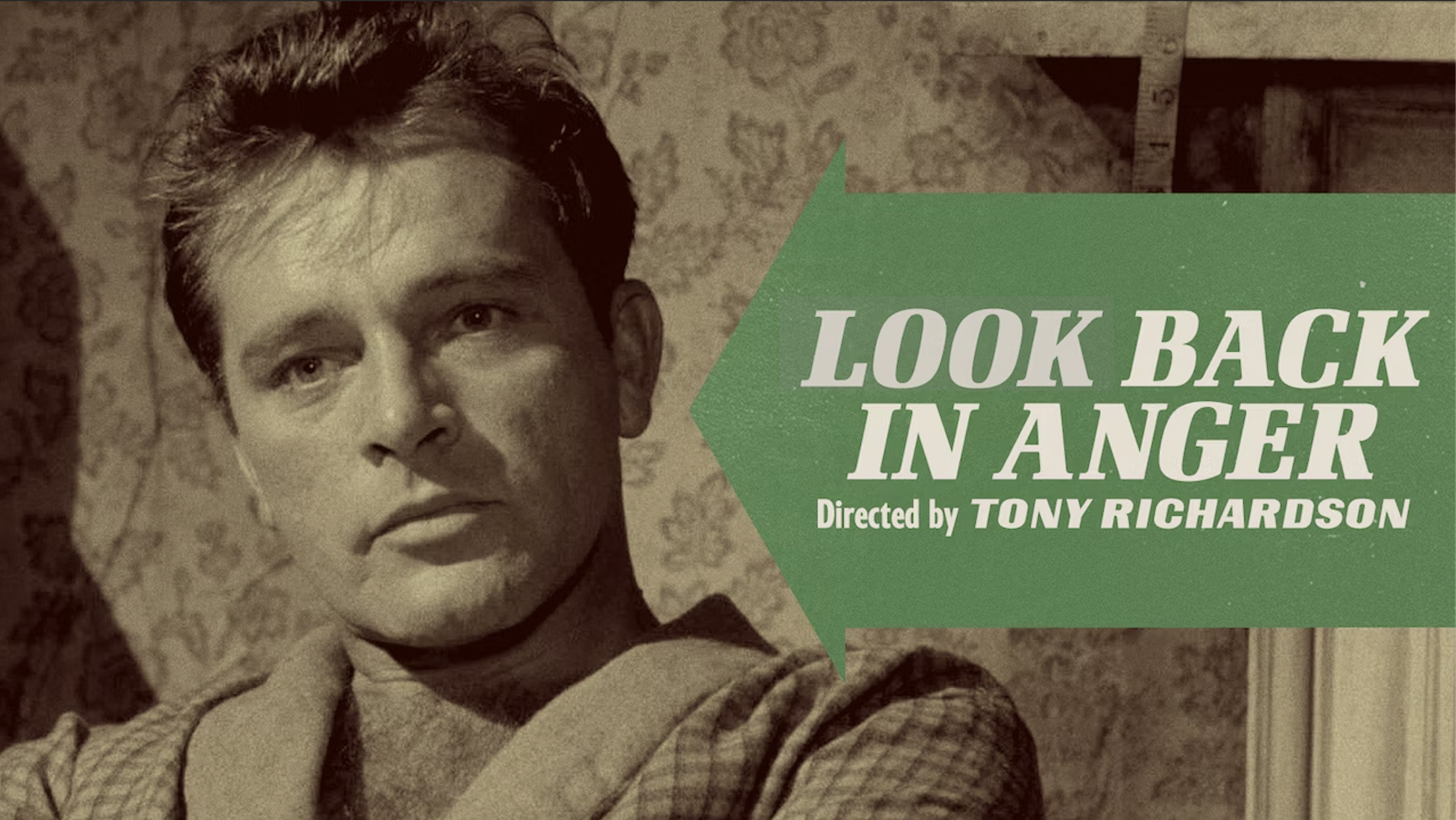

Look Back in Anger (1959)

John Osborne’s theatre of cruelty and misery exploded on to the English stage in 1956. Look Back in Anger was adapted for the movie screen three years later by veteran writer and Quatermass creator Nigel Kneale and directed by Tony Richardson. It now has a cinema rerelease, and maybe what it reminded me of right away was Robert Hamer’s It Always Rains on Sunday. In this film, it always seems to be Sunday, and it’s raining. The sheer choking sadness of the postwar British Sabbath is what comes across here most immediately – its meteorology of gloom. There’s nothing to do but feel listless and angry and read the raucous but somehow insidiously depressing Sunday newspapers. And the nastiness and casual racism of 1950s Britain is exposed here in a way that most British cinema was too tactful to notice.

Viewed again almost 60 years on from its original release, what strikes you is how conservative this film seems, not how revolutionary. Some of the confrontations and dialogue belong to precisely that Rattiganesque genteel world that Osborne wanted to put a bomb under. Maybe the line readings are a bit stilted, just occasionally. The movie opens out the stage play by placing many scenes at the local railway station, very obviously borrowing ideas from David Lean’s Brief Encounter. The film version loses that insolent symmetry of act one and act three: one woman submissively doing the ironing, and then another – though on screen as on stage, the idea of two beautiful women successively entranced by a sexily bad tempered brute looks like a very unexamined male fantasy. But there’s no doubt that Richard Burton gives some firepower to those famous rant speeches, arias of self-hate and rage that might otherwise be overpoweringly shrill and petulant.

He is Jimmy Porter, a brooding malcontent who lives in a cramped attic flat with his upper-class wife, Alison, played by a somewhat frozen Mary Ure. The third wheel is their lodger, Cliff, forthrightly played by Gary Raymond. He is Jimmy’s mate and willing straight man for all Jimmy’s self-admiring comedy routines and music-hall gags. It hardly needs saying that Cliff is a sort of wife to Jimmy as well. As their desolate rainy Sunday stretches ahead, and Alison placidly does the ironing, enraging Jimmy with her martyred silence, their tiny room is the scene of explosive and despairing outbursts.

The awful truth is that Jimmy obsesses about being of a lower social class than Alison, to use a creepy upper-middle-class phrase of the time, he “minds” about it. The bit-of-rough frisson that once fired their relationship is in decline. Jimmy accuses Alison of snobbery because he has snobbishly assessed himself and found himself wanting. He is a university graduate and now all he does in life is run a sweet stall with Cliff, an intense humiliation. When Alison announces that her actress friend Helena (Claire Bloom) is coming to stay, Jimmy is predictably chippy and obnoxious, but the stage is set for some Kowalskian steam heat.

Burton’s Jimmy is a nasty piece of work, and what is still so subversive about him is his simple, endless, directionless and almost motiveless rudeness: he’s a hero for the trolling world of the social media 21st century. Jimmy is not violent, but his kind of obsessive self-harming rage is disturbing. This movie has him storm on to the local theatre stage where Helena is rehearsing her polite drawing-room drama to take the mickey out of it. An unthinkable piece of pure ill-mannered spite, which incidentally discloses Jimmy’s not-so-secret envy for the world of show business success. He himself plays jazz trumpet at a local club occasionally, but does not appear to have the discipline or concentration to make anything more of it.

The great success of Richardson’s film version of Look Back in Anger is the amplification of the Ma Tanner figure, the cheerful woman who lent Jimmy the money to set up his stall: she is played by Edith Evans. Evans’s performance humanises Jimmy Porter – and humanises Burton’s performance as well. Jimmy loves the old lady like a mother, although, boorish curmudgeon that he is, he can’t help converting these tender and vulnerable feelings into scorn for his wife, obtusely accusing her of being cold to Mrs Tanner. This relationship between Ma Tanner and Jimmy is poignant and even tragic, gives a sympathy and depth to Porter that might not otherwise be there.

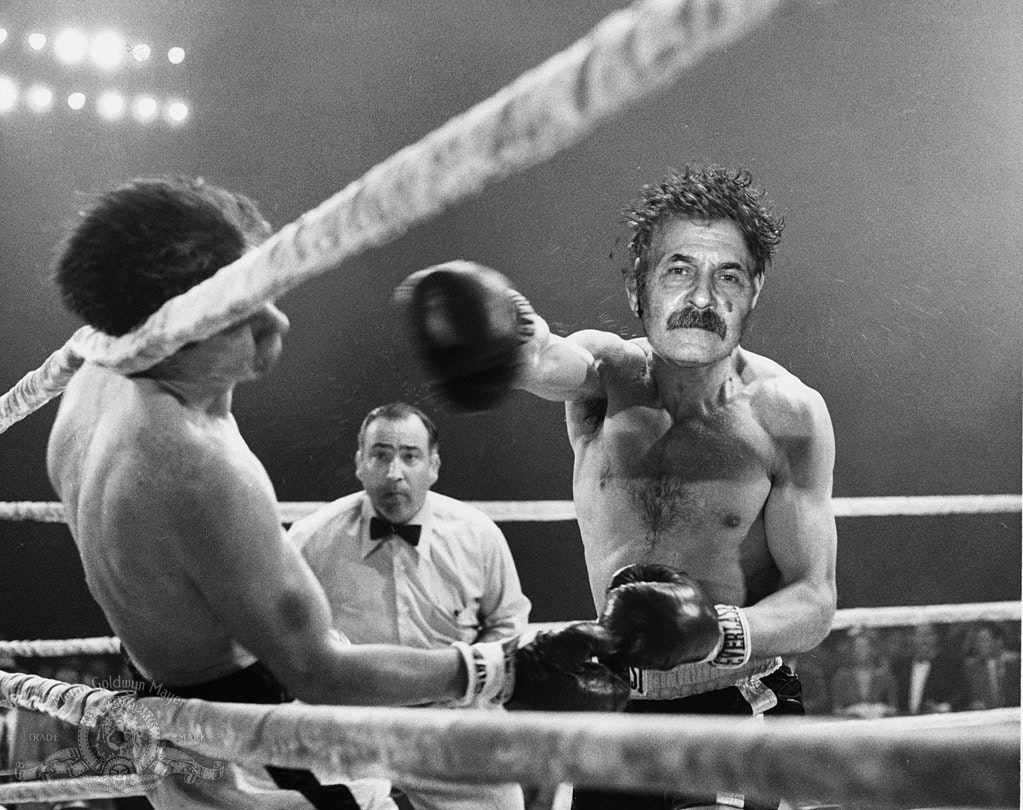

RAGING BULL (1980)

“Raging Bull” is not a film about boxing but about a man with paralyzing jealousy and sexual insecurity, for whom being punished in the ring serves as confession, penance and absolution. It is no accident that the screenplay never concerns itself with fight strategy. For Jake LaMotta, what happens during a fight is controlled not by tactics but by his fears and drives.

Consumed by rage after his wife, Vickie, unwisely describes one of his opponents as “good-looking,” he pounds the man's face into a pulp, and in the audience a Mafia boss leans over to his lieutenant and observes, “He ain't pretty no more.” After the punishment has been delivered, Jake (Robert De Niro) looks not at his opponent, but into the eyes of his wife (Cathy Moriarty), who gets the message.

Martin Scorsese's 1980 film was voted in three polls as the greatest film of the decade, but when he was making it, he seriously wondered if it would ever be released: “We felt like we were making it for ourselves.” Scorsese and De Niro had been reading the autobiography of Jake LaMotta, the middleweight champion whose duels with Sugar Ray Robinson were a legend in the 1940s and '50s. They asked Paul Schrader, who wrote “Taxi Driver,” to do a screenplay. The project languished while Scorsese and De Niro made the ambitious but unfocused musical “New York, New York,” and then languished some more as Scorsese's drug use led to a crisis. De Niro visited his friend in the hospital, threw the book on his bed, and said, “I think we should make this.” And the making of “Raging Bull,” with a screenplay further sculpted by Mardik Martin (“Mean Streets”), became therapy and rebirth for the filmmaker.

The movie won Oscars for De Niro and editor Thelma Schoonmaker, and also was nominated for best picture, director, sound, and supporting actor (Joe Pesci) and actress (Moriarty). It lost for best picture to “Ordinary People,” but time has rendered a different verdict.

For Scorsese, the life of LaMotta was like an illustration of a theme always present in his work, the inability of his characters to trust and relate with women. The engine that drives the LaMotta character in the film is not boxing, but a jealous obsession with his wife, Vickie, and a fear of sexuality. From the time he first sees her, as a girl of 15, LaMotta is mesmerized by the cool, distant blond goddess, who seems so much older than her age, and in many shots seems taller and even stronger than the boxer.

Although there is no direct evidence in the film that she has ever cheated on him, she is a woman who at 15 was already on friendly terms with mobsters, who knew the score, whose level gaze, directed at LaMotta during their first date, shows a woman completely confident as she waits for Jake to awkwardly make his moves. It is remarkable that Moriarty, herself 19, had the presence to so convincingly portray the later stages of a woman in a bad marriage.

Jake has an ambivalence toward women that Freud famously named the “Madonna-whore complex.” For LaMotta, women are unapproachable, virginal ideals--until they are sullied by physical contact (with him), after which they become suspect. During the film he tortures himself with fantasies that Vickie is cheating on him. Every word, every glance, is twisted by his scrutiny. He never catches her, but he beats her as if he had; his suspicion is proof of her guilt.

The closest relationship in the film is between Jake and his brother Joey (Joe Pesci). Pesci's casting was a stroke of luck; he had decided to give up acting, when he was asked to audition after De Niro saw him in a B movie. Pesci's performance is the counterpoint to De Niro's, and its equal; their verbal sparring has a kind of crazy music to it, as in the scene where Jake loses the drift of Joey's argument as he explains, “You lose, you win. You win, you win. Either way, you win.” And the scene where Jake adjusts the TV and accuses Joey of cheating with Vickie: “Maybe you don't know what you mean.” The dialogue reflects the Little Italy of Scorsese's childhood, as when Jake tells his first wife that overcooking the steak “defeats its own purpose.”

The fight scenes took Scorsese 10 weeks to shoot instead of the planned two. They use, in their way, as many special effects as a science fiction film. The soundtrack subtly combines crowd noise with animal cries, bird shrieks and the grating explosions of flashbulbs (actually panes of glass being smashed). We aren't consciously aware of all we're listening to, but we feel it.

The fights are broken down into dozens of shots, edited by Schoonmaker into duels consisting not of strategy, but simply of punishing blows. The camera is sometimes only inches from the fists; Scorsese broke the rules of boxing pictures by staying inside the ring, and by freely changing its shape and size to suit his needs--sometimes it's claustrophobic, sometimes unnaturally elongated.

The brutality of the fights is also new; LaMotta makes Rocky look tame. Blows are underlined by thudding impacts on the soundtrack, and Scorsese uses sponges concealed in the gloves and tiny tubes in the boxers' hair to deliver spurts and sprays of sweat and blood; this is the wettest of boxing pictures, drenched in the fluids of battle. One reason for filming in black and white was Scorsese's reluctance to show all that blood in a color picture.

The most effective visual strategy in the film is the use of slow motion to suggest a heightened awareness. Just as “Taxi Driver's” Travis Bickle saw the sidewalks of New York in slow motion, so LaMotta sees Vickie so intently that time seems to expand around her. Normal movement is shot at 24 frames a second; slow motion uses more frames per second, so that it takes longer for them to be projected; Scorsese uses subtle speeds such as 30 or 36 frames per second, and we internalize the device so that we feel the tension of narrowed eyes and mounting anger when Jake is triggered by paranoia over Vickie's behavior.

The film is bookmarked by scenes in which the older Jake LaMotta, balding and overweight, makes a living giving “readings,” running a nightclub, even emceeing at a Manhattan strip club. It was De Niro's idea to interrupt the filming while he put on weight for these scenes, in which his belly hangs over his belt. The closing passages include Jake's crisis of pure despair, in which he punches the walls of his Miami jail cell, crying out, “Why! Why! Why!”

Not long after, he pursues his brother down a New York street, to embrace him tenderly in a parking garage, in what passes for the character's redemption--that, and the extraordinary moment where he looks at himself in a dressing room mirror and recites from “On the Waterfront” (“I coulda been a contender”). It's not De Niro doing Brando, as is often mistakenly said, but De Niro doing LaMotta doing Brando doing Terry Malloy. De Niro could do a “better” Brando imitation, but what would be the point?

“Raging Bull” is the most painful and heartrending portrait of jealousy in the cinema--an “Othello” for our times. It's the best film I've seen about the low self-esteem, sexual inadequacy and fear that lead some men to abuse women. Boxing is the arena, not the subject. LaMotta was famous for refusing to be knocked down in the ring. There are scenes where he stands passively, his hands at his side, allowing himself to be hammered. We sense why he didn't go down. He hurt too much to allow the pain to stop.

More reading:

https://cinephiliabeyond.org/raging-bull/

THE BAD AND THE BEAUTIFUL (1952)

In the early 1950s, as the big studio system breathed its last, Hollywood produced a succession of classic Tinseltown fables: Sunset Boulevard, In a Lonely Place, Singin' in the Rain, The Barefoot Contessa, A Star Is Born and, right in the middle, The Bad and the Beautiful, made in 1952 and back in the cinemas to accompany a Minnelli retrospective at the NFT. Though directed with Minnelli's characteristic delicacy, this is essentially a producer's film, made by John Houseman, one of the great figures of 20th-century American theatre and cinema. Houseman's first Hollywood job was supervising the script of Citizen Kane, his second was working for David O Selznick. In The Bad and the Beautiful, Houseman applies a similar structure, intelligence and suavity to a ruthless Hollywood genius much like Selznick as he brought to Charles Foster Kane.

An old-style Hollywood studio boss (Walter Pidgeon) brings together a movie star (Lana Turner), a major director (Barry Sullivan) and a Pulitzer-prize author (Dick Powell) to see if they'll work again with Jonathan Shields (Kirk Douglas). A producer now down on his luck, Shields simultaneously built their careers and nearly destroyed their lives. Each recalls their experience of Shields, and in the course of an immaculately cast and acted film they paint a warts-and-all portrait of Hollywood at its zenith, a tale of how the bad created something beautiful. Charles Schnee won an Oscar for his script, as did Gloria Grahame for her performance as a ditzy southern belle, Robert Surtees for his black-and-white cinematography and Edward Carfagno for his production design. David Raksin, author of the title song for Laura and onetime pupil of Arnold Schoenberg, should have got an Oscar for his score.

FIST OF FURY (1972)

His early martial arts films broke Box Office records in Hong Kong and portrayed martial arts in an entirely new light. The success of his films attracted the attention of Hollywood—Bruce Lee’s “Enter the Dragon” was the first Hollywood/Hong Kong co-production, starting the martial arts film craze in the USA. Despite his early death, he remains a legend in the martial arts world.

However, while Bruce Lee is indisputably a martial arts icon, his martial arts filmography is relatively small. Prior to his death, he was only involved in five action films, though “Game of Death” and “Enter the Dragon” were released posthumously. While “Enter the Dragon” is his most famous, “Fist of Fury” is his best.

Bruce Lee plays Chen Zen, a martial arts student who learns that his beloved teacher has been murdered and seeks to extract vengeance and restore the honour of his school. Set during the Japanese occupation of China, there is intense racial tension and Chinese nationalism throughout the film. The Japanese repeatedly taunt and insult Chen and the Chinese people. Chen’s rage and violence is not only to restore honour to his school, but also to his nation.

The fight scenes in ‘Fist of Fury’ are among the best of Lee’s career. The first dojo fight scene, where Chen challenges an entire room of Japanese karate fighters, is incredible. Lee punches and kicks faster than the eye can see and his ability with the nunchucks is remarkable.

Bruce Lee in a scene from “Fist of Fury” (Golden Harvest Company, 1972).

His presence on-screen is powerful and immense, which the director utilizes to great effect. In the opening sequence, Chen enters a funeral in a stark white suit, standing out amidst the mourners clothed in black. The visual stylings of the fight scenes are similarly striking, often placing Chen Zen, shirtless and wearing black pants, surrounded by Japanese fighters in white karate outfits.

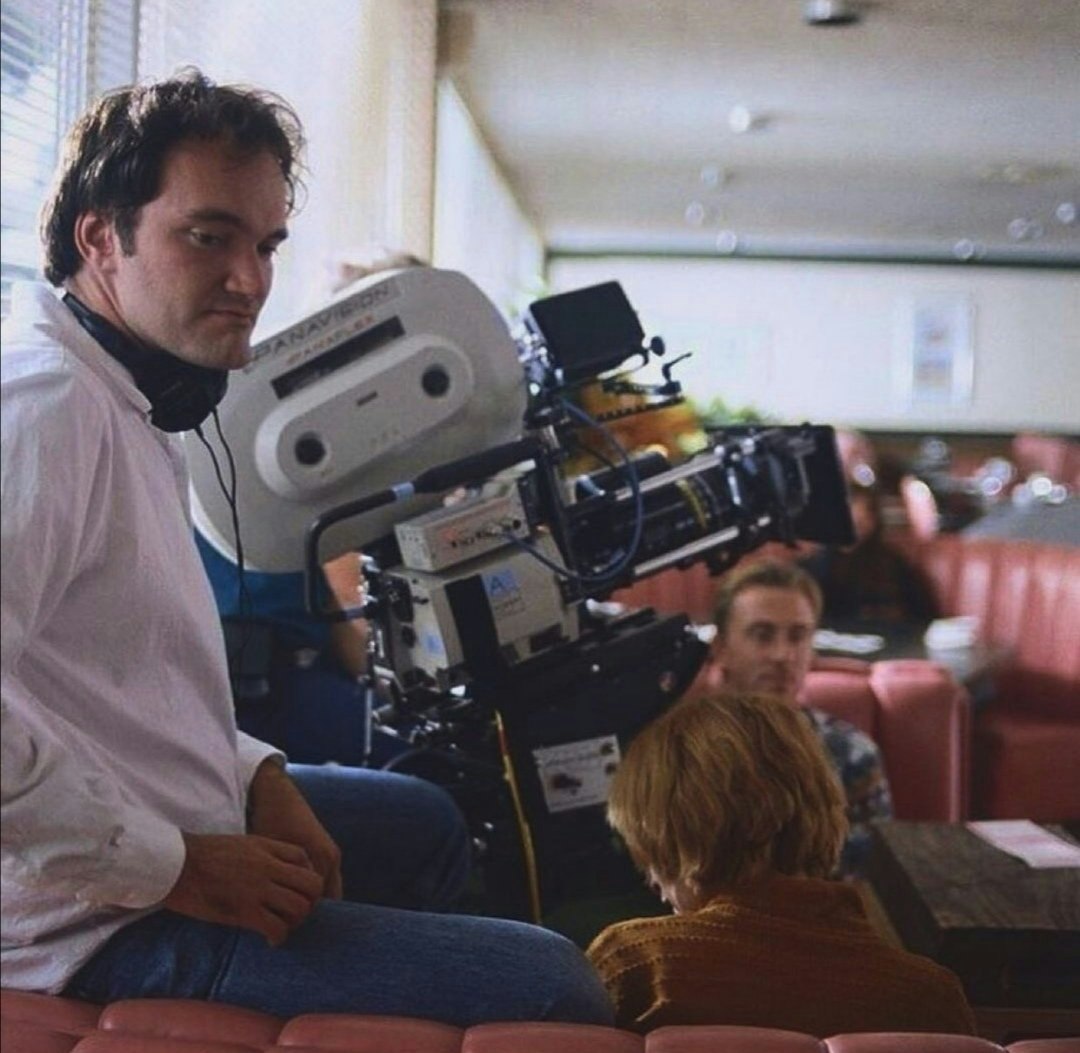

With the lone hero fighting to protect the community against an oppressive force, this film borrows many tropes from Western movies. In fact, the film’s score is reminiscent of Ennio Morricone’s spaghetti westerns. When paired with the striking visuals, it is easy to see how films like “Fist of Fury” may have influenced directors like Quentin Tarantino.

While there are obvious wins, there are also definite flaws in this film. Ludicrously bad dubbing affects the majority of early martial arts films, including this one, and the film is rough around the edges, as the script, direction, and acting are all unpolished and cheesy at times. Additionally, though there are less tonal problems here than the rest of Lee’s films, the romantic sub-plot is a little forced and there are some out-of-place humorous moments, such as when Lee dresses in costume to avoid detection.

In sum, Bruce Lee is a genuine star and “Fist of Fury” is arguably his best film, while suffering from the many issues plaguing early martial arts films. Though not a cinematic masterpiece, it is a must-watch for fans of martial arts movies and the legendary Bruce Lee.

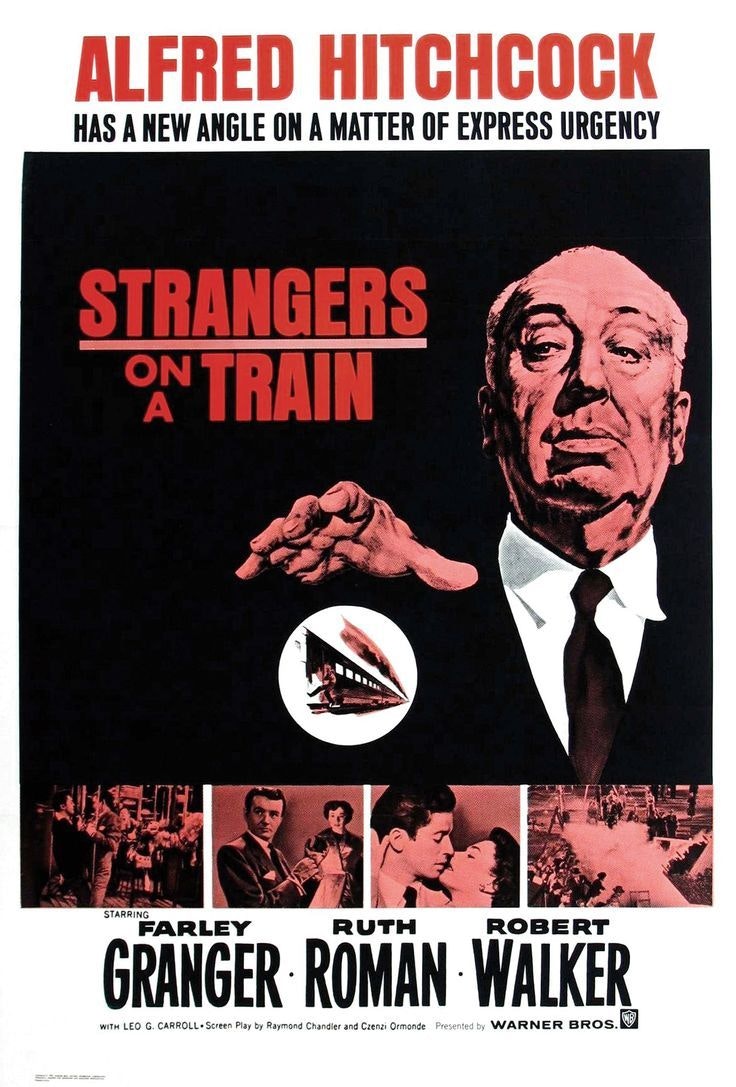

LIFEBOAT (1944)

Made right during the middle of WWII, Lifeboat was the first of Alfred Hitchcock’s experiments with movies set in a single enclosed space: a lifeboat after a shipwreck. It was filmed in the studio for maximum focused artificiality. The movie starts off in an uncomfortably didactic fashion (John Steinbeck did the original story, and his heavy hand can sometimes be felt), but Lifeboat is actually much more complicated than it first appears. Its emphasis on moral debates in dialogue can seem a little dry, but Hitchcock’s shifting sympathies guarantee our guilty involvement with the characters until he builds to a climax of intellectual and spiritual excitation.

It starts with a ship going down, and we see various objects floating away: a copy of The New Yorker, playing cards, wooden spoons, a chessboard, and finally a corpse. With this sobering sight, Hitchcock switches to a wider view of the detritus, but he chokes off any easy emotions of pity for disaster with a cut to his film-long joke: glamorous Tallulah Bankhead sitting alone in a lifeboat. Bankhead, a flamboyant theater star who never made much of a Hollywood impression, is granted a peculiar showcase here, her only decent one. Bankhead’s eyes are inexpressive, and the camera doesn’t really like her, but Hitchcock does and we eventually warm to her; like many theatrical personalities, she does most of her acting with her (comically low) voice. Her Constance Porter is a journalist, and she whips out a camera to film the survivors as they climb into the boat (a pointed bit of self-criticism from film-mad Hitchcock). “Look, that’s a perfect touch!” she cries, trying to take film of a baby’s abandoned bottle. This enrages Kovac (John Hodiak), the resident socialist, and he throws her camera overboard (the first in a long line of things Connie loses throughout the film).

As Hitchcock introduces the other characters, we can palpably feel his impatience with most of them. There’s low-class Brit Stanley (Hume Cronyn), natty capitalist C. D. Rittenhouse (Henry Hull), dopey Gus (William Bendix), reformed pickpocket Joe (Canada Lee), pretty nurse Miss MacKenzie (Mary Anderson), Mrs. Higgins (Heather Angel), a mad woman with a dead baby, and Willy (Walter Slezak), a corpulent Nazi. They discuss whether or not to throw Willy overboard; Kovac wants to pitch him out right away, but Connie and Rittenhouse argue in his defense, citing the laws of democracy and the precepts of Christianity. Hitchcock gets in a nice dig against racism when Joe, who’s black, quietly asks if he gets to vote on the matter. Joe, who is devoutly Christian, says a prayer in the dark of night (a beautiful shot), and Hitchcock balances his faith and dignity with Willy’s obvious craft and cunning. Meanwhile, Mrs. Higgins keeps flipping out. Though her scenes are handled with gravity and tact, when Willy yawns at her stagy anguish, we can’t help but feel that Hitchcock is yawning too.

Intellectually, we know we’re supposed to be horrified by Willy’s callousness, the same callousness we’re supposed to find amusing in Connie. Hitchcock subverts these expected responses so that we actually loathe Connie at first and side with Willy’s no-nonsense strength. The yawn is the first time we’re made to identify with Willy, which implicates us in his treachery later on. Hitchcock never puts his audience at a distance from his characters; we’re always being confronted by ourselves and our attitudes because of his masterful manipulation of various points of view. His serial killers, like Bruno Anthony and Norman Bates, are always the most attractive, sympathetic characters in his films. That’s why Willy (and Nazism itself) is given its fair shake, which is what makes Lifeboat so disturbing. What film today would dare to hint at anything positive in fascism, even if it’s just to strengthen a case against it? Yet Hitchcock doesn’t even really make that expected case. He’s above such things; in Lifeboat, he’s hunting bigger, cosmic game. There’s no playfulness here and precious little humor. This is a serious, at times self-serious movie (though the director’s cameo, a newspaper ad for diet pill Reduco, stands with his bus-misser in North by Northwest as his most amusing film appearance).

Gus and his gangrenous leg take over the film for a while, and Hitchcock has Bendix overplay his dumb-lug persona. Hitch emphasizes everyone’s unpleasant condescension to this thickheaded fool; his drunk scene while he waits for them to cut his leg off is painfully indulgent. The actor (and character) is so unbearable that our responses are complicated yet again after Willy pushes him out of the boat (it’s suggested he did the same for Mrs. Higgins). When the others voice their outrage at his actions, Willy sounds seductively practical as he says that he was only doing a favor for the poor cripple (and a favor for the audience by getting rid of Bendix). If Hitchcock had made a film set in a concentration camp, he would have probably focused on a very unattractive inmate, made us hate them by casting someone unlikable and hammy, made us feel guilty for hating this noble victim, and compounded that guilt by making the Nazi commandant a charming, charismatic fascist who gases children all day and then goes home to play Schubert with unerring skill and proper feeling. Evil, Hitchcock knows, is tempting. Which is why it proliferates and always will.

Hitchcock underlines the passenger’s mob ugliness when they kill Willy. (In his interview with François Truffaut, he called them “a pack of dogs.”) They don’t just throw Willy overboard: They beat on him wildly with their fists, and this charge is led by the gentle-featured Miss MacKenzie. It’s been revealed that she’s having an affair with a married man, and for a moment it seems that Hitch’s attraction/repulsion to lady-like sluts has gotten the better of him. However, it ultimately feels quite right that she should start the violence. And not “she of all people.” Hitchcock has taught us to distrust appearances.

We’re made to see that Willy’s “survival of the fittest” ethic is abhorrent and that the capitalism that’s made Rittenhouse’s fortune is this monstrous ethic taken to its financial extreme. Rittenhouse professes that he’s broken up about becoming part of a lynch mob, but he should be more broken up about the traits he shares with Willy. No one gets off here; everyone is guilty. Finally, Joe looks up to God for guidance, and Hitchcock, sensibly enough, is all for this. If you look at the world as deeply as Hitchcock does, religion really is your only answer. Like so many of his movies, Lifeboat is a deeply Catholic work.

Catholicism is linked strongly to the carnal, of course, and Hitchcock really goes for this subtext in most of his filmography, but only at moments here, such as the scene when Connie rubs the top of her foot over Kovac’s sole. Hitchcock eventually brings salacious Bankhead into focus as the film’s emblem. We get to like her character more as she’s stripped of her material accoutrements, in the same way Melanie Daniels is humanized by suffering in The Birds. Hitch is drawn to Tallulah’s wildness; too shy to celebrate it, he breaks it down, finds out its components, and likes what he sees (she doesn’t need to be punished too much, unlike the submissive Tippi Hedren). Connie has sympathy for the nurse’s troubles, she kisses Gus before his leg is cut off (a lusty, open-mouthed Tallulah kiss), kisses Kovac when they think they’re going to die (open-mouthed with a bit of tongue), and gives a definitive answer to Joe’s prayer: “How about giving Him a hand?” she asks.

This line, a platitude, really (“God helps those who help themselves”), is utterly resonant as a summing up of the film’s complicated points of view. It’s also a thunderbolt incitement for the Allied side in WWII, fighting a war that needed to be won. Perhaps the repetition of the young German getting on board and instantly pulling a gun on them is a little much (or maybe it just happens too abruptly). But Hitchcock has one more jolt up his sleeve in Rittenhouse’s reaction: “You can’t treat them as human beings, you have to exterminate them!” he says, echoing Nazi rhetoric. Hitch gives pagan goddess Connie the last word. Her lipstick retouched, ready to join the messy world again and live with Tallulah-esque gusto, she wisely refuses to answer the many slippery problems raised in the film and invokes God the father, the ying to her yang, who, she suggests, has a lot of explaining to do.

MORE INFO:

https://cinephiliabeyond.org/a...

EL ESPIRITU DE LA COLMENA (SPIRIT OF THE BEEHIVE)

In a vast Spanish plain, harvested of its crops, a farm home rests. Some distance away there is a squat building like a barn, apparently not used, its doors and windows missing. In the home lives a family of four: two little girls named Ana and Isabel, and their parents, Fernando and Teresa. He is a beekeeper, scholar and poet who spends much time in his book-lined study. She is a solitary woman who writes letters of longing and loss to men not identified. The parents have no conversations of any consequence.

It’s an exciting day in the village. A ramshackle truck rattles into town announced by scampering children, who shout, “The movies! The movies!” A screen and projector are set up in the public hall, and an audience of kids and old women gather to see “Frankenstein” (1931).

For the children, the movie had might as well only be about the monster, so tellingly performed by Boris Karloff. The creature comes upon a farmer’s young daughter tossing flowers into a pond to watch them float. Perhaps because of censorship, the film cuts directly from this to the monster mournfully carrying the child’s drowned body through the village. Perhaps because of censorship, we don’t see that he did not drown her, but threw her in with delight, thinking she would float as well. For the two girls, especially Ana (Ana Torrent), this makes a dramatic impression.

Her misunderstanding of the scene will shape the events to follow in Victor Erice’s “The Spirit of the Beehive” (1973), believed by many to be the greatest of all Spanish films. Although the time is not specified, it would have been clear to Spanish audiences that the film is set soon after the end of the Spanish Civil War, which began Franco’s long dictatorship — so soon after that the same day, a wounded opponent of the regime takes refuge in the barn-like outbuilding.

Only a few years separate Ana and Isabel (Isabel Telleria), but they form that important divide where Ana depends on her big sister to explain mysteries. The little girl runs carefree all over the farmlands, and in the barn she discovers the wounded soldier. That night, her eyes wide open in the dark, she asks Isabel to explain why the creature drowned the little girl. “Everything in the movies is fake,” she’s told. “It’s all a trick. Besides, I’ve seen him alive. He’s a spirit.” That of course serves for Ana as a possible explanation for the wounded man, and the next day, she sneaks him some food and water, and her father’s coat.

What follows is considered a coded message about Franco’s fascist regime, but it’s not for me to connect the dots. I relate to it more strongly as a poetic work about the imagination of children, and how it can lead them into mischief and sometimes rescue them from its consequences.

“The Spirit of the Beehive” is one of only three features and a short subject directed by Erice (born 1940). Like such films as Charles Laughton’s “The Night of the Hunter” (1955), it is a masterpiece that can only cause us to wonder what we lost because he didn’t work more. It is simple, solemn, and in the casting of young Ana Torrent, takes advantage of her open, innocent features. We can well believe her when she accepts her sister’s explanation, which goes far to account for her behavior later in the film.

This is one of the most beautiful films I’ve seen. Its cinematographer, Luis Cuadrado, bathes his frame in sun and earth tones, and in the interiors of the family home, he creates vistas of empty rooms where footsteps echo. The house doesn’t seem much occupied by the family. The girls are often alone. The parents also, in separate rooms. Many of the father’s poems involve the mindless churning activity of his beehives, and the house’s yellow-tinted honeycomb windows make an unmistakable reference to beehives. Presumably this reflects on the Franco regime, but when critics grow specific in spelling out the parallels they see, I feel like I’m reading term papers.

More rewarding is to read the surface of the film. When Ana’s good intentions to the “spirit” are misinterpreted, and when she is linked to the wounded man by her father’s pocket watch, this sets up a situation that could be dangerous for both father and daughter. When she runs away and inspires a search — the lanterns of volunteers bobbing through the night — we feel how the behavior of innocent children can lead them into trouble. In a later scene when Ana plays a trick on Isabel, the older child also discovers how her myth-making has repercussions.

Ana Torrent starred in another notable Spanish film, Carlos Saura’s “Cria Cuervos” (1976). She has gone on to a successful career, making 45 films and TV series, including Saura’s “Elisa, My Life” (1977), his first film after Franco’s fall. But child actors are often bathed in a glow of enchantment that no later role will quite capture.

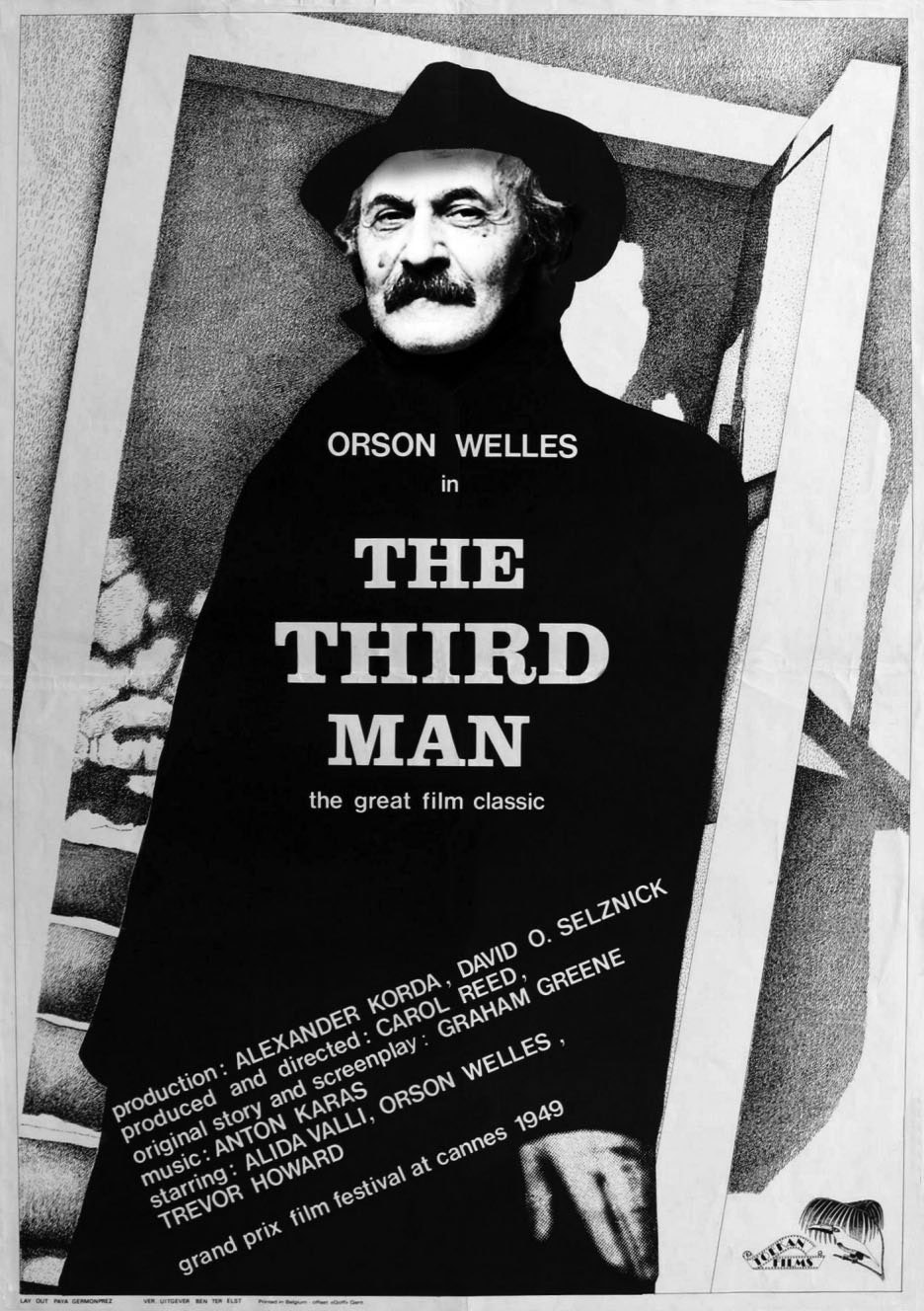

THE LADY FROM SHANGHAI

There's such outrageous brilliance in Orson Welles's brash and sexy noir melodrama from 1947, now on re-release. There are some opaque plot tangles, perhaps due to 60 minutes being cut from Welles's original version by the studio, but the sheer brio and style make it a thing of wonder, whisking the audience from the streets of New York City, to the open seas, to a tense courtroom and then to a bizarre house of mirrors.

This is arguably Welles's best acting performance: theatrically romantic, with warmth, wit and a gust of pure charisma. He plays O'Hara, an Irish merchant seaman induced to sign on as part of the crew of a luxury yacht belonging to wealthy lawyer Bannister (Everett Sloane), having fallen in love with his young wife Elsa (Rita Hayworth) – a beautiful woman with a shady past in the far east whom Bannister evidently blackmailed into marrying him. Soon O'Hara is mixed up in a murderous plot cooked up by Bannister's partner Grisby (Glenn Anders). Welles creates a dreamlike (though never surrealist) fluency and strangeness, along with a salty tang of black comedy and an electric current of doom and desire between O'Hara and Elsa. It has an irresistible energy.

Find out more about Orson with these BBC documentaries:

TO JOIN OUR MAILING LIST EMAIL US AT:

EMAIL: info@cine-real.com

INSTAGRAM - cinereal16mm

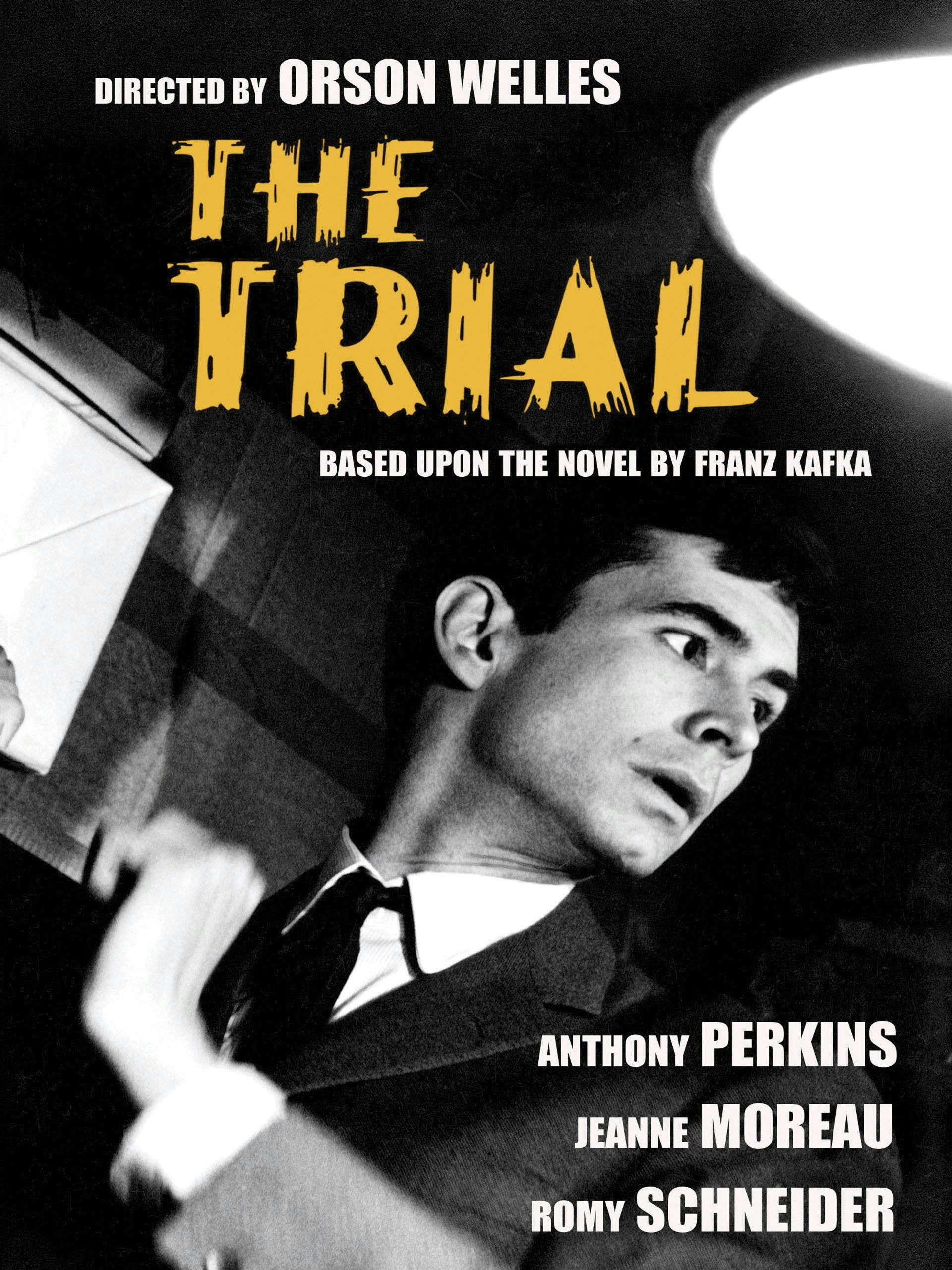

THE TRIAL (1963)

Roger Ebert was once involved in a project to persuade Orson Welles to record a commentary track for "Citizen Kane." Seemed like a good idea, but not to the Great One, who rumbled that he had made a great many films other than "Kane" and was tired of talking about it.

One he might have talked about was "The Trial" (1963), his version of the Franz Kafka story about a man accused of--something, he knows not what. It starred Anthony Perkins in his squirmy post- "Psycho" mode, it had a baroque visual style, and it was one of the few times, after "Kane," when Welles was able to get his vision onto the screen intact. For years, the negative of the film was thought to be lost, but then it was rediscovered, restored and plays at the Film Center this weekend.