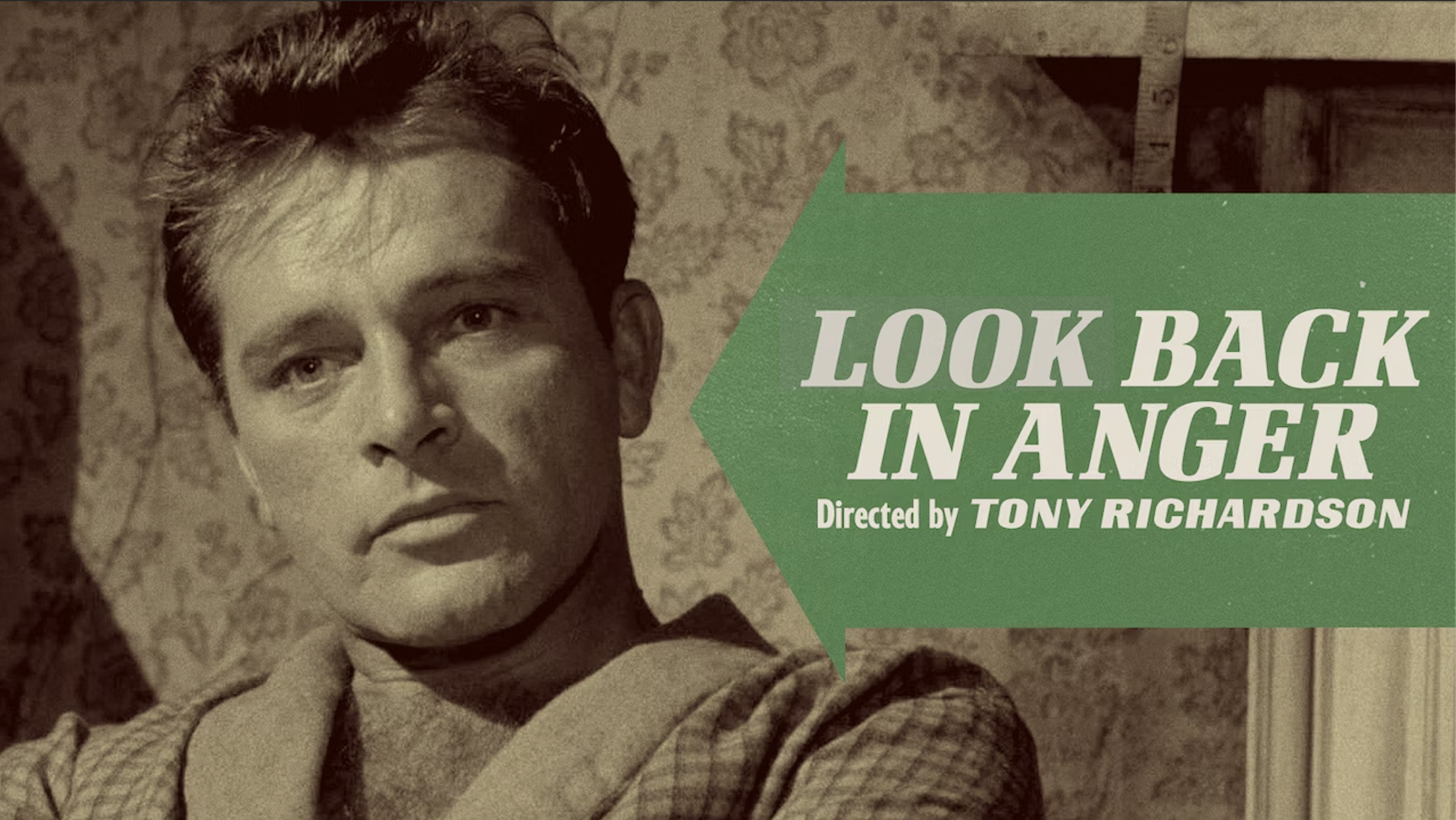

Look Back in Anger (1959)

Look Back in Anger (1959)

John Osborne’s theatre of cruelty and misery exploded on to the English stage in 1956. Look Back in Anger was adapted for the movie screen three years later by veteran writer and Quatermass creator Nigel Kneale and directed by Tony Richardson. It now has a cinema rerelease, and maybe what it reminded me of right away was Robert Hamer’s It Always Rains on Sunday. In this film, it always seems to be Sunday, and it’s raining. The sheer choking sadness of the postwar British Sabbath is what comes across here most immediately – its meteorology of gloom. There’s nothing to do but feel listless and angry and read the raucous but somehow insidiously depressing Sunday newspapers. And the nastiness and casual racism of 1950s Britain is exposed here in a way that most British cinema was too tactful to notice.

Viewed again almost 60 years on from its original release, what strikes you is how conservative this film seems, not how revolutionary. Some of the confrontations and dialogue belong to precisely that Rattiganesque genteel world that Osborne wanted to put a bomb under. Maybe the line readings are a bit stilted, just occasionally. The movie opens out the stage play by placing many scenes at the local railway station, very obviously borrowing ideas from David Lean’s Brief Encounter. The film version loses that insolent symmetry of act one and act three: one woman submissively doing the ironing, and then another – though on screen as on stage, the idea of two beautiful women successively entranced by a sexily bad tempered brute looks like a very unexamined male fantasy. But there’s no doubt that Richard Burton gives some firepower to those famous rant speeches, arias of self-hate and rage that might otherwise be overpoweringly shrill and petulant.

He is Jimmy Porter, a brooding malcontent who lives in a cramped attic flat with his upper-class wife, Alison, played by a somewhat frozen Mary Ure. The third wheel is their lodger, Cliff, forthrightly played by Gary Raymond. He is Jimmy’s mate and willing straight man for all Jimmy’s self-admiring comedy routines and music-hall gags. It hardly needs saying that Cliff is a sort of wife to Jimmy as well. As their desolate rainy Sunday stretches ahead, and Alison placidly does the ironing, enraging Jimmy with her martyred silence, their tiny room is the scene of explosive and despairing outbursts.

The awful truth is that Jimmy obsesses about being of a lower social class than Alison, to use a creepy upper-middle-class phrase of the time, he “minds” about it. The bit-of-rough frisson that once fired their relationship is in decline. Jimmy accuses Alison of snobbery because he has snobbishly assessed himself and found himself wanting. He is a university graduate and now all he does in life is run a sweet stall with Cliff, an intense humiliation. When Alison announces that her actress friend Helena (Claire Bloom) is coming to stay, Jimmy is predictably chippy and obnoxious, but the stage is set for some Kowalskian steam heat.

Burton’s Jimmy is a nasty piece of work, and what is still so subversive about him is his simple, endless, directionless and almost motiveless rudeness: he’s a hero for the trolling world of the social media 21st century. Jimmy is not violent, but his kind of obsessive self-harming rage is disturbing. This movie has him storm on to the local theatre stage where Helena is rehearsing her polite drawing-room drama to take the mickey out of it. An unthinkable piece of pure ill-mannered spite, which incidentally discloses Jimmy’s not-so-secret envy for the world of show business success. He himself plays jazz trumpet at a local club occasionally, but does not appear to have the discipline or concentration to make anything more of it.

The great success of Richardson’s film version of Look Back in Anger is the amplification of the Ma Tanner figure, the cheerful woman who lent Jimmy the money to set up his stall: she is played by Edith Evans. Evans’s performance humanises Jimmy Porter – and humanises Burton’s performance as well. Jimmy loves the old lady like a mother, although, boorish curmudgeon that he is, he can’t help converting these tender and vulnerable feelings into scorn for his wife, obtusely accusing her of being cold to Mrs Tanner. This relationship between Ma Tanner and Jimmy is poignant and even tragic, gives a sympathy and depth to Porter that might not otherwise be there.